For Senate Leaders, Conflicts Take A Personal Turn And Play Out In Public

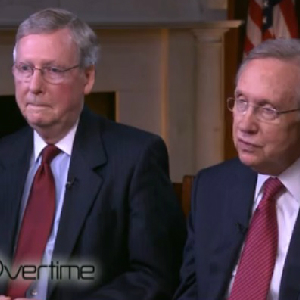

SCREENSHOT

WASHINGTON (MCT) — Four minutes after the Senate returned from its Fourth of July recess last week, Harry Reid laced into Mitch McConnell.

Senate Republican leaders were throwing a “temper tantrum,” Reid told the Senate. Their conduct was “outrageous.”

Once uncommon, it was another ugly yet routine day in the dysfunctional U.S. Senate. Reid and McConnell can barely stand each other.

Their feud echoes America’s political mood: Polarized. Angry. Untrusting. And it’s a key reason Congress doesn’t work.

Routine spending bills are caught in the maelstrom, stalled in a standoff that could trigger another showdown in September over funding the Federal government. In one pivotal dispute, Reid is making it harder for McConnell, a Kentucky Republican, to pass a proposal that would help would his State’s coal industry.

Also hanging in the gridlock: the highway trust fund, which might run out of money as soon as next month, and talks to help the troubled Department of Veterans Affairs.

Traditionally, Senate leaders take the lead in ending these conflicts. Yet Reid, the Senate majority leader and Nevada Democrat, and McConnell, the minority leader, have met just once since December. They instead engage in public, often personal spats on the Senate floor. And their exchanges feature bile-rich dialogue rare in modern times from the chamber’s most powerful figures.

Political Journeys

The political journeys of both men hardly seemed destined for such opposite directions. Congressional leaders usually reach these jobs because they’re consensus-builders adept at accommodating the disparate interests of a broad political party, and often had to endure hardship and conflict to succeed and survive politically at home.

McConnell, 72, spent his early years in Alabama, overcame polio as a child and moved as a teenager with his family to Louisville. He was a student of the Senate from an early age, interning during college for one Kentucky Senator and later working as an aide for another.

He won his seat in 1984, by four-tenths of a percentage point at a time that fellow Republican Ronald Reagan was taking the State by more than 20 points in his landslide re-election. In four subsequent re-elections, McConnell’s won more than 55 percent only once. This year, he’s engaged in another too-close-to-call struggle, against Democrat Alison Lundergan Grimes, the Kentucky secretary of state.

Reid, 74, grew up in the hardscrabble town of Searchlight, Nev. His father was an alcoholic who committed suicide at age 58, and the family never had it easy. Reid became a boxer whose coach was Mike O’Callaghan, later Nevada’s governor. Reid worked as a U.S. Capitol Police officer to help pay for law school, and back in Nevada was elected O’Callaghan’s lieutenant governor at age 30.

Reid lost his first Senate bid, in 1974. Twelve years later, he won the seat with 50 percent of the vote, and was re-elected in 1992 with 51 percent. In 1998, Reid barely survived, winning by 428 votes. In 2010, he fought off a strong challenge from Tea Party favorite Sharron Angle, winning with 50.2 percent.

In Washington, Reid and McConnell largely shunned the media spotlight, instead crafting reputations as deal-makers and vote-counters. Reid easily won the election among his peers to be the Democratic leader in 2004. McConnell smoothly ascended to Republican leader two years later, also winning an open spot.

Seasoned Pros

Seasoned pros, the two showed early signs of a traditional leadership relationship. They talked often, usually face to face, and helped craft deals that allowed major legislation through Congress such as the Troubled Asset Relief Program, which helped save the financial industry in 2008, and aid to the ailing auto industry.

“Behind the scenes, in the places where cameras do not record our discussions, as we have to have, we are not only friends but determined partners in the legislative process,” Reid told the Senate on Jan. 12, 2009.

Eight days later, President Barack Obama took office, and the Senate’s tone changed.

Obama quickly pushed costly new government programs that rankled Republicans, such as the $787 billion stimulus for the economy, a sweeping plan to combat climate change and a vast overhaul of health care.

By the time Obama got to healthcare, McConnell was marshaling forces for an extraordinary campaign to block it. Though in the minority, he could use the threat of a filibuster to deny Reid the 60 votes the majority would need to proceed.

McConnell’s procedural tactics helped force votes during snowstorms, after midnight and in one case 20 minutes before dawn on Christmas Eve.

McConnell was proud of his tactics. He was playing rough, but by the rules.

Reid fumed. He saw McConnell as defying tradition. Sure, you push hard; but you don’t make people come in on Christmas Eve, not when you know the bill is going to pass anyway.

Nor do you use those procedural tactics on what should be routine matters, such as letting a President appoint lower-level Federal judges as long as they were legally qualified.

By last summer, Reid was moving toward an extraordinary step.

Changing The Rules

He took the pulse of Senate Democrats about changing the rules to curb the minority’s power.

Newer members such as Senator Jeff Merkley of Oregon were adamant. The old traditions were stifling. Republicans were playing hardball, and Democrats had to play the same game. “The American people want this institution to function,” Merkley said.

Veterans such as Senator Carl Levin (D-Mich.) balked. The idea being floated — allowing 51 votes to cut off debate in many cases, instead of 60 — might make Senate life easier for Democrats in 2013, but in a few years Republicans could have control and much more power.

Reid was losing sleep.

He usually went back to his condominium in the Foggy Bottom neighborhood of Washington and relaxed watching baseball. He liked the Washington Nationals, which had the pride of Las Vegas, outfielder Bryce Harper, as their up-and-coming star.

Even baseball couldn’t distract Reid now. He was torn. McConnell would probably relent on the judges, but the Senate was looking dysfunctional and little was getting done.

McConnell, though, showed no signs of relenting. McConnell plays the Senate like a poker player. His face, his tone, his demeanor betray nothing. Even after all these years, Reid found him hard to read.

Reid grew consumed by the fight.

Last July 11, after the opening prayer and the Pledge of Allegiance, Reid rose to his front-row podium, his glasses slightly crooked.

He recalled that McConnell had pledged to “work with the majority to process nominations.”

Reid stared straight ahead, his voice barely rising. “Those were his words. Those were his commitments. Those were his promises,” he said. “By any objective standard, he has broken them.”

It was an extraordinarily personal criticism, rare in the modern Senate. McConnell stood across the aisle, with his expressionless gaze.

“What this is about is manufacturing a pretext for a power grab,” McConnell said.

Code Of Conduct

Long known as for its clublike atmosphere, the Senate runs by a code of conduct: Don’t make enemies. Learn to disagree without being disagreeable.

Reid now thought that code breached. The stalling didn’t just involve judges. It seemed to touch everything Obama wanted.

Still uneasy about where he might be headed, Reid looked past McConnell for an agreement to let the Senate vote on some of the President’s nominations for appointments and avoid the “nuclear option” of curbing the filibuster.

He appealed to Senator John McCain (R-Ariz.), the famously independent operator.

Over the weekend, McCain told Reid he could deliver the half-dozen Republican votes needed to proceed with some of the deadlocked nominations, notably Richard Cordray as the director of the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau. The deal: Obama had to withdraw two of the National Labor Relations Board nominees who Republicans felt were illegally appointed.

(Last month, the Supreme Court ruled that the President did improperly make three NLRB nominations, including those that were withdrawn.)

On a Monday night last July, Reid called a meeting of all Senators in the Old Senate Chamber, on the second floor of the Capitol. Last used regularly in 1859, it was the site of historic debates over slavery and territorial expansion.

They met privately for four hours. Levin warned fellow Democrats that they won’t always be in the majority. Afterward, Democratic leaders headed to Reid’s office down the hall, where they ate pretzel sticks and trail mix from the big tubs Reid has in his office. Changing the rules didn’t feel right.

They called McCain. He was still willing to deal, and he agreed to go ahead with several votes, including four executive branch nominees.

Reid’s security detail drove him home to his condo in a black SUV. There was no baseball on to relax him. Still, he slept soundly.

A Last-Ditch Offer

Tuesday morning, Reid took his usual half-hour morning walk near his home. He talked to McCain on the phone, then called other Senators.

Just before the Senate was to convene at 10 a.m., McConnell left his office and marched down the hall on the Capitol’s second floor, past the big picture windows with their postcard views of the Washington Monument.

He made a left, then a right, then was in Reid’s office. He made a last-ditch offer: I’ll agree to the controversial nominee if you’ll make a public statement saying you won’t change the rules to weaken the filibuster. Reid said no.

Reid went to the Senate floor and praised McCain. McCain, in turn, praised Reid. Aware that he couldn’t stop it, McConnell publicly embraced the deal.

This wasn’t over.

Sure enough, in November, the test case came. This time it involved three D.C. Circuit Court judges and Representative Mel Watt, Obama’s nominee for the Federal Housing Finance Agency.

Republicans said he wasn’t qualified. Democrats saw an attempt to embarrass a popular veteran Congressman.

McCain this time couldn’t help. Republicans found the judges too ideological and had serious qualms about Watt’s ability to run the agency.

Reid dug in. This time, some former skeptics such as Senator Patrick Leahy (D-Vt.) said go.

On the Senate floor, colleagues from both parties urged Reid to reconsider. By changing the rules, “we will have sacrificed a professed vital principle for the sake of momentary gain,” warned Levin.

Reid wouldn’t budge. “Can anyone say the Senate is working now?” he asked the Senate. “I don’t think so.”

The Senate voted 52-48 to change the rules to require 51 votes to limit debate on most judicial and executive branch nominees.

Outside the Senate chamber, McConnell ripped the move. “Democrats set up one set of rules for themselves and another for everybody else.”

The Reid-McConnell Feud

The two men met in December and then not again until May 1, when they had a general discussion of issues in Reid’s Capitol office. That’s been it. They’ve spent the year battling.

Now, the Reid-McConnell feud threatens the budget deal reached in the wake of last year’s shutdown of the Federal government and might plunge Washington back into fiscal brinksmanship.

The House of Representatives has been smoothly, quietly writing detailed spending plans this year; and the Senate was doing the same.

But last month, Reid said he wanted 60 votes to amend some spending bills, instead of the usual 51 — after he insisted that most of Obama’s nominees not be subject to 60-vote rules.

McConnell sought a vote on his proposal to curb Obama Administration plans to more tightly regulate carbon emissions from current coal-fired plants. The proposal would help his State’s coal industry.

Reid said McConnell’s plan was a major policy change and, thus, should need 60 votes for approval. McConnell had embraced the 60-vote rule to slow measures, Reid charged, so he should be subjected to the same approach.

“Since he’s been the minority leader, virtually everything we do around here has had a 60-vote hurdle,” Reid said. “That’s why we call it the McConnell rule.”

McConnell objected to the change of approach to amendments on spending bills.

Reid pulled the bill. Progress on spending stalled. And since the Senate plans to be out of session from Aug. 1 until Sept. 8 and the fiscal year ends Sept. 30, chances of passing any legislation looked grim.

Insiders thought one chance might be that tempers would cool during the nine-day Fourth of July recess that ended July 7. Instead, Reid apparently stewed through the break, and was eager to pounce the minute he got back to the Senate.

“Instead of saying their needless obstruction has hurt us,” Reid told the Senate as he spoke of the past and future, “the Republican leadership has responded with what can only be described as a temper tantrum.”

McConnell tersely offered his view the next day to reporters.

“We’d have a better chance of working our way through the bills that we need to pass,” McConnell said, “if we cut out the showboats and didn’t eat up time trying to score points for the fall elections.”

–David Lightman

McClatchy Washington Bureau

McClatchy Washington Bureau

No comments:

Post a Comment

Thanks for commenting. Your comments are needed for helping to improve the discussion.