The chaos in Baghdad explains why Obama isn't trying to destroy ISIS

Iraqi Prime Minister Nouri al-Maliki threw the country's political system into crisis on Sunday, when he announced that he would be staying on as Prime Minister after a deadline to form a new government expired without an agreement at 12 am Baghdad time. Maliki announced a plan to sue Iraq's President, Fuad Masum, for violating the country's constitution, and it's now totally unclear when, if ever, Iraq will return to normal democratic procedures.

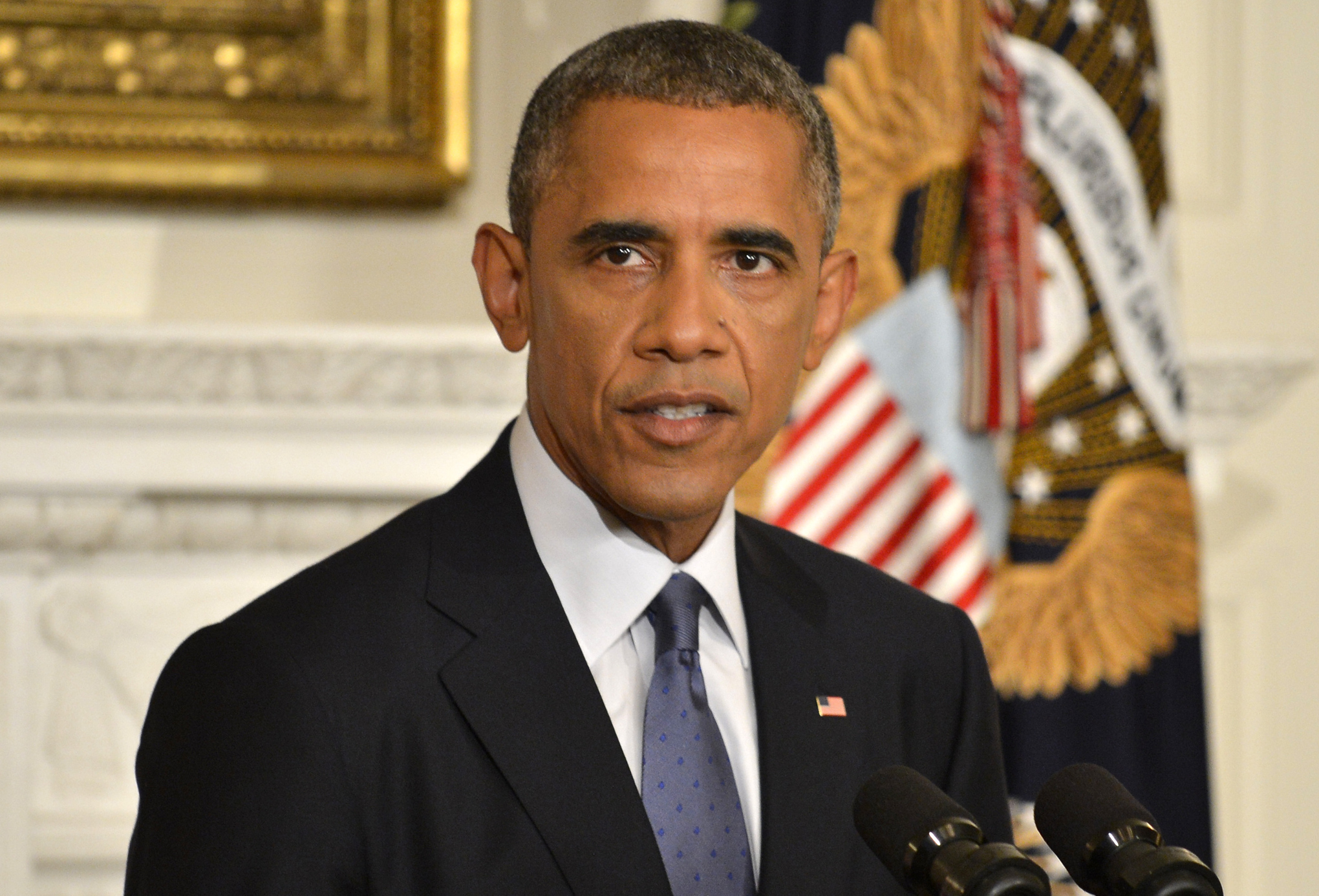

All of this underscores why, on his Saturday press conference about the US intervention on Iraq, President Obama emphasized the need for Iraqi political reform to solve the ISIS crisis. "Ultimately, there's not going to be an American military solution to this problem," President Obama told reporters. "There's going to have to be an Iraqi solution." This is the key line to understand if you want to grasp the administration's approach to Iraq — and why the goals of the US military campaign are more narrow than you might think.

The American objectives for Obama's airstrikes in Iraq are very clear, and very limited. American airpower will protect Iraqi Kurdistan from the advance of militants from Islamic State (ISIS), and will attempt to break the ISIS siege that's starving up to 40,000 members of the Yazidi minority on an isolated mountain.

So why is the US stopping there? ISIS controls a huge swath of land about the size of Belgium in Iraq and Syria. The group poses a serious threat to the Iraqi government and possibly even the stability of the entire region. If the United States can beat ISIS back in Kurdistan, why not elsewhere?

That line about an Iraqi solution is the administration's answer. In fact, the Obama administration has been consistent on this question since June, when ISIS first took control of big chunks of Iraq. They see ISIS as, at its heart, a political problem — one that can't be solved solely with force. But the march on Kurdistan and the siege on Sinjar are narrow military problems, and thus merit military solutions. This distinction between military and political problems is at the heart of the Obama administration's thinking on Iraq.

ISIS is more of a political problem than a military problem

An Iraqi soldier. Stringer/Anadolu Agency/Getty Images

ISIS isn't just a terrorist group rampaging through Iraq (though they definitely are that). It's in many ways an expression of the Sunni Muslim minority's anger at the Shia-dominated government. Sunnis are the minority in Iraq, and based mostly in the country's northern half, and have seen their political power decline since the 2003 US-led invasion toppled the Sunni government, which is now mostly Shia.

"The Sunnis have lots of different grievances," Kirk Sowell, a political risk analyst and expert on Iraqi politics, says. Some of these are the current government's fault. Prime minister Maliki has treated the Sunnis badly, including forcibly breaking up a peaceful protest movement in 2013. His seemingly authoritarian turn on Sunday shows just how far Maliki remains from moving towards a more inclusive style of governance.

Some Sunni grievances get to more fundamental issues within the Iraqi state itself, beyond what even a better government could easily fix. "Even if Maliki weren't in power, there are some Sunni grievances that any Shia government would have problems with [trying to resolve]," Sowell says. This includes a widespread, but false, belief among Sunnis that they're the actual demographic majority, and so are entitled to more political power then they have in Iraqi politics.

While these grievances of course don't transform Iraqi Sunnis into ISIS-style theocrats, it does make Sunni communities more open to at least seeing if ISIS will be better for them than Baghdad. And so long as ISIS has at least passive support from the Sunni population, it will be almost impossible for the Iraqi government to dislodge them from the mostly Sunni territory they hold.

"The main animator behind sectarian competition in Iraq," according to Fanar Haddad, a research fellow at the National University of Singapore's Middle East Institute, is the "question of how you divide the national pie." Who gets how much oil money, how many seats each sectarian group has in parliament, and so on.

If Sowell and Haddad are right, then no amount of military force on its own would be likely to solve Iraq's crisis. Even if ISIS loses popular support, Sunni unrest against the central government is inevitable until Iraq's broader political problems are resolved. ISIS isn't the only Sunni militia fighting the government, after all.

The US wants political reform before any broader military campaign

Obama announcing the Iraq strikes. Mike Theiler-Pool/Getty Image

The Obama administration clearly shares the assessment that Iraq needs political reforms, not just military action, to end the crisis. "Absent Sunni buy in, [ISIS] will be hard to dislodge," a senior administration official said after Obama announced the Kurdistan bombing campaign. "Part of the reason we're focused on the Iraqi government is if we get a more inclusive government that opens the way to broader support."

Since June, the president has been clear about what that assessment means for military campaigns. "The US is not simply going to involve itself in a military action in the absence of a political plan by the Iraqis," Obama said in a June 13 address. He was more blunt in Saturday's presser, saying "the nature of this problem is not the one our military can solve."

Unless the Iraqi government seriously addresses Sunni grievances, American airstrikes won't solve the ISIS problem. So that's why the US isn't going to try to solve the larger ISIS problem with airstrikes — they believe it wouldn't work.

"The broken internal politics of Iraq make it deeply vulnerable to ISIS and that needs to be fixed," Douglas Ollivant, the head of the National Security Council for Iraq from 2005-2009, told me earlier in the crisis. Ollivant thinks temporary strikes to blunt ISIS's momentum against the Iraqi government could be justified, but that they shouldn't be seen a substitute for Iraqi political reform.

And that's exactly how the administration is thinking about the strikes just in and around Kurdistan.

Why Kurdistan is different

Kurdish peshmerga. Safin Hamed/AFP/Getty Images

"[ISIS] is going to need to be rolled back," the senior administration official said, but "the first step is breaking their momentum."

Right now, their momentum is in Sinjar and Kurdistan. ISIS is engaged in a conventional war for territory against the Kurdish militias, called peshmerga, and has won some serious victories on the battlefield. The US wants to stop them.

According to Ollivant, ISIS is harder to target when they're tucked away in bases or cities. But when "they come out of their hole, the US air force can destroy them in detail." In order to seize more territory in Kurdistan, or make a move toward the Kurdish capital Erbil, ISIS will have to move across open terrain where they're vulnerable to Kurdish-directed US airstrikes.

Stopping this advance is a fundamentally different problem from rolling back ISIS altogether. It's best, just for the purposes of understanding the US airstrikes, to think of semi-autonomous Kurdistan as an entirely separate country from the rest of Iraq. The US goal isn't to fix the ISIS problem; it's to repel the invasion of Kurdistan.

The US's humanitarian objective in Sinjar, outside of Kurdistan, is similarly narrow. ISIS fighters control all of the roads in and out of Mount Sinjair, which is why the 10,000-plus Yazidis trapped there are starving to death. The US airforce could help the peshmerga should they launch an open battle to clear some of those roads.

But those are the limits of the operation, at least for now. Obama's speech didn't commit the US to ending all of the fighting in Iraq or pushing back ISIS entirely. The administration is thinking, very narrowly, about accomplishing a specific military objective — break the siege — that would help save lives. Anything more than that would involve a much more involved military campaign.

Of course, the US began the war in Libya, at least nominally, as a campaign to stop a slaughter in Benghazi. That escalated to much broader war aimed at toppling Qaddafi. But it doesn't seem like Obama thinks that destroying ISIS is an end that US military power alone can accomplish.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Thanks for commenting. Your comments are needed for helping to improve the discussion.