One Iranian Family’s Fight to Keep a

Colorado City From

Taking Their Property

Nasrin Kholghy, left, and her family own Authentic Persian and Oriental Rugs in Glendale, Colo. The city threatened to take their store, along with other property they own, through eminent domain. (Photo: Nasrin Kholghy)

When Nasrin Kholghy opened the letter from the

city of Glendale, Colo., in April, it transported her

back to another country in another time.

city of Glendale, Colo., in April, it transported her

back to another country in another time.

The letter notified Kholghy of an upcoming city

council meeting.

council meeting.

There, Glendale’s leaders would be voting to

approve the use of a tool that would give them

the power to take Kholghy’s property and

transform it into a planned retail, entertainment,

and dining redevelopment project.

approve the use of a tool that would give them

the power to take Kholghy’s property and

transform it into a planned retail, entertainment,

and dining redevelopment project.

The news brought Kholghy back to Iran, the

country she emigrated from alone in the 1970s.

country she emigrated from alone in the 1970s.

“When I got the letter of them being able to use

eminent domain, I really, really felt—we lost a

lot of land in Iran when the revolution happened,

” Kholghy said. “I thought, ‘Oh my gosh, it’s

happening again. We’re losing it again.’”

eminent domain, I really, really felt—we lost a

lot of land in Iran when the revolution happened,

” Kholghy said. “I thought, ‘Oh my gosh, it’s

happening again. We’re losing it again.’”

Eminent domain is a power given to the

government to take private property for a

public use. In Kholghy’s case, the city had

its eyes on six acres of property her family

owned.

government to take private property for a

public use. In Kholghy’s case, the city had

its eyes on six acres of property her family

owned.

The property contains the family’s 30-year-old

rug business, Authentic Persian and Oriental

Rugs.

rug business, Authentic Persian and Oriental

Rugs.

Last month, the city offered to buy the Kholghys’

property for $11 million. But the family rejected

the offer, saying instead they wanted to remain

in the community they’ve called home since

Kholghy came to the United States 40 years ago.

property for $11 million. But the family rejected

the offer, saying instead they wanted to remain

in the community they’ve called home since

Kholghy came to the United States 40 years ago.

“I have memories of our kids jumping on rug piles.

They pretended the floor was lava,” Kholghy said

in an interview with The Daily Signal. “We’ve had customers who’ve done that, and they bring their

kids. The same person who jumped on the rugs,

they bring their kids to jump on the rugs. It’s not

were just going to take this money and go away.”

They pretended the floor was lava,” Kholghy said

in an interview with The Daily Signal. “We’ve had customers who’ve done that, and they bring their

kids. The same person who jumped on the rugs,

they bring their kids to jump on the rugs. It’s not

were just going to take this money and go away.”

Nasrin Kholghy looks at some of the rugs she sells at

Authentic Persian and Oriental Rugs. (Photo: Nasrin Kholghy)

Authentic Persian and Oriental Rugs. (Photo: Nasrin Kholghy)

Humble Beginnings

It’s difficult not to smile when speaking to

Kholghy about her start in the United States.

Kholghy about her start in the United States.

The oldest of five, Kholghy laughs as she

remembers details about her younger years.

remembers details about her younger years.

In her early 20s, when she was just getting

started in the industry, Kholghy confronted and

challenged a rug shop owner.

started in the industry, Kholghy confronted and

challenged a rug shop owner.

“I told him I would open a shop and ‘put you

out of business,’” Kholghy recalls. “Sometimes

you forget [those] things.”

out of business,’” Kholghy recalls. “Sometimes

you forget [those] things.”

The Iranian woman has had the same phone

number since 1976—”nobody else has that

long-running of a phone number,” she said—

and still remembers the exact date she arrived

in the United States from Iran: Jan. 6, 1975.

number since 1976—”nobody else has that

long-running of a phone number,” she said—

and still remembers the exact date she arrived

in the United States from Iran: Jan. 6, 1975.

Kholghy traveled to the States with her mother,

who returned to Iran a month later, leaving

Kholghy alone to learn English in Trinidad,

Colo., and pursue an American education.

who returned to Iran a month later, leaving

Kholghy alone to learn English in Trinidad,

Colo., and pursue an American education.

Over the next four years, Kholghy settled into

her life in the United States. She got married

to her husband, Mozy Hemmati, at the close of

1975, and the couple graduated together from the University of Colorado Denver four years later.

her life in the United States. She got married

to her husband, Mozy Hemmati, at the close of

1975, and the couple graduated together from the University of Colorado Denver four years later.

After graduation, Kholghy and her husband

decided to remain stateside, as the revolution

in Iran had broken out while they were in school.

decided to remain stateside, as the revolution

in Iran had broken out while they were in school.

By 1979, three of Kholghy’s four siblings had

joined their oldest sister in the United States,

and they all lived together in a home in Glendale,

Colo., which the family still owns today.

joined their oldest sister in the United States,

and they all lived together in a home in Glendale,

Colo., which the family still owns today.

Then, 52 Americans were held hostage in Tehran,

and it became impossible for Kholghy’s parents

to send their children money.

and it became impossible for Kholghy’s parents

to send their children money.

But Kholghy’s dad found a way to help his kids.

“My father called and said, ‘The only thing that

Iran is letting out is rugs, so I’m going to send

you guys some rugs, and then sell them and

eat and go to school and pay tuition. Just use

it,’” Kholghy recalled.

Iran is letting out is rugs, so I’m going to send

you guys some rugs, and then sell them and

eat and go to school and pay tuition. Just use

it,’” Kholghy recalled.

When the first rugs arrived from Iran, Kholghy

tried to sell them to other stores.

tried to sell them to other stores.

She opened the Yellow Pages, found the

largest ad for rugs she could find and made an appointment. But after a bad experience with

the store’s owner—the same man she vowed

to put out of business—Kholghy found herself

outside of an empty storefront in the Cherry

Creek Shopping Center.

largest ad for rugs she could find and made an appointment. But after a bad experience with

the store’s owner—the same man she vowed

to put out of business—Kholghy found herself

outside of an empty storefront in the Cherry

Creek Shopping Center.

The building was set to be demolished, and

management told Kholghy they were no longer

leasing.

management told Kholghy they were no longer

leasing.

She offered to lease the space for just one day,

one week, one month—the amount of time

didn’t matter—so long as Kholghy had a place

to sell the rugs her father had sent from Iran.

one week, one month—the amount of time

didn’t matter—so long as Kholghy had a place

to sell the rugs her father had sent from Iran.

Kholghy’s pleas worked, and she began leasing

the space.

the space.

“We didn’t even know what they were worth,”

she said of the Persian rugs her father sent.

“We just sold them for whatever people paid

for them.”

she said of the Persian rugs her father sent.

“We just sold them for whatever people paid

for them.”

Now more than three decades later, what

began as a temporary way for the Kholghy’s

to pay their college tuition has grown into a

full-time business, Authentic Persian and

Oriental Rugs.

began as a temporary way for the Kholghy’s

to pay their college tuition has grown into a

full-time business, Authentic Persian and

Oriental Rugs.

“Oh, my God, we got lucky,” Kholghy said,

looking back at how her business began.

“People came.”

looking back at how her business began.

“People came.”

Adding To the Land

For the last 25 years, the Kholghys have been

running their business on roughly an acre of

property located on one of the busiest streets in the Denver area.

running their business on roughly an acre of

property located on one of the busiest streets in the Denver area.

The family runs the store together. In 2006,

they officially purchased their property and

the adjacent five acres of land, which they

now lease to a hair salon, marijuana shop,

car dealership, and detail center.

they officially purchased their property and

the adjacent five acres of land, which they

now lease to a hair salon, marijuana shop,

car dealership, and detail center.

“We’ve always had a feeling that this area

could be much nicer, better, with more stuff,”

Kholghy said. “We thought of adding little

things to the land.”

could be much nicer, better, with more stuff,”

Kholghy said. “We thought of adding little

things to the land.”

In 2007, the family decided to put together

a plan to spruce up their property, drafting a redevelopment plan that included 11

condominiums on top of two stories of

restaurants and shops, including their

own store, Authentic Persian and Oriental Rugs.

a plan to spruce up their property, drafting a redevelopment plan that included 11

condominiums on top of two stories of

restaurants and shops, including their

own store, Authentic Persian and Oriental Rugs.

The Kholghy family attempted to work with the city to redevelop

the property they own in Glendale, Colo. The city rejected their

plans and unveiled their own proposal that didn’t include

Authentic Persian and Oriental Rugs. (Photo: Nasrin Kholghy)

the property they own in Glendale, Colo. The city rejected their

plans and unveiled their own proposal that didn’t include

Authentic Persian and Oriental Rugs. (Photo: Nasrin Kholghy)

It was Kholghy’s dream to live in one of the condos overlooking the business she built, which she knew

her own children would take over eventually.

her own children would take over eventually.

“I had in my head that when I retire and I’m old,

I can be upstairs and still watch over [the family],”

Kholghy said.

I can be upstairs and still watch over [the family],”

Kholghy said.

The family submitted the plan to the city, which

considered but eventually rejected it.

considered but eventually rejected it.

“After talking back and forth with them, it became

apparent they weren’t going to let us do anything

we wanted,” Kholghy said. “They’re going to find

a way to say no.”

apparent they weren’t going to let us do anything

we wanted,” Kholghy said. “They’re going to find

a way to say no.”

Dreams Demolished: 10 Years After the

Government Took Their Homes, All That’s

Left Is an Empty Field

Government Took Their Homes, All That’s

Left Is an Empty Field

‘It’s Happening All Over Again’

Just before the city of Glendale sent the

Kholghys the letter notifying them about the

potential for condemnation, officials

unveiled Glendale 180, “a dining and entertainment

development that reestablishes Glendale’s position

as the essential social hub of the Denver area.”

Kholghys the letter notifying them about the

potential for condemnation, officials

unveiled Glendale 180, “a dining and entertainment

development that reestablishes Glendale’s position

as the essential social hub of the Denver area.”

The 42-acre project is projected to cost $175 million

and, according to a map of the proposed site

released by the city, is situated on property

that includes the land the Kholghys own.

and, according to a map of the proposed site

released by the city, is situated on property

that includes the land the Kholghys own.

After unsuccessful negotiations, the Glendale

City Council voted in May to give the city’s

Urban Renewal Authority the power to use

eminent domain for the Kholghys’ six acres

of land.

City Council voted in May to give the city’s

Urban Renewal Authority the power to use

eminent domain for the Kholghys’ six acres

of land.

“I felt like it’s happening all over again, and I

felt what my father must’ve felt when they took

all his land in Iran,” Kholghy said.

felt what my father must’ve felt when they took

all his land in Iran,” Kholghy said.

The city is projected to break ground this fall.

A city official declined to make Mayor Mike

Dunafon and members of the city council

available for interviews because of pending

litigation.

A city official declined to make Mayor Mike

Dunafon and members of the city council

available for interviews because of pending

litigation.

The city unveiled a plan for Glendale 180, a dining,

entertainment and retail space, in April. That same month,

Glendale officials sent Nasrin Kholghy a letter letting her

know the city council would be voting to approve the use

of eminent domain to take her property. (Photo: Glendale 180)

entertainment and retail space, in April. That same month,

Glendale officials sent Nasrin Kholghy a letter letting her

know the city council would be voting to approve the use

of eminent domain to take her property. (Photo: Glendale 180)

Post-Kelo Takings

The last clause of the Fifth Amendment, the

Takings Clause, gives the government the

power to condemn land through eminent domain

if it satisfies two conditions: first, it’s for a public

use, and second, the owner of the land must

receive just compensation.

Takings Clause, gives the government the

power to condemn land through eminent domain

if it satisfies two conditions: first, it’s for a public

use, and second, the owner of the land must

receive just compensation.

Historically, public use constituted the taking

of property for a school, bridge, or road—

an entity that benefited the public.

of property for a school, bridge, or road—

an entity that benefited the public.

However, in 2005, the U.S. Supreme Court

broadened the definition of public use in the

controversial case Kelo v. City of New London.

According to the high court’s ruling, the

government has the right to use eminent

domain to transfer property from one private

party to another private party for economic

development so long as just compensation

is provided.

broadened the definition of public use in the

controversial case Kelo v. City of New London.

According to the high court’s ruling, the

government has the right to use eminent

domain to transfer property from one private

party to another private party for economic

development so long as just compensation

is provided.

The ruling became one of the most despised

in the court’s history.

in the court’s history.

In the wake of the Kelo decision, more than

40 states passed laws limiting the use of

eminent domain for transfers to private parties.

In 11 of those states, the legislature passed

constitutional amendments.

40 states passed laws limiting the use of

eminent domain for transfers to private parties.

In 11 of those states, the legislature passed

constitutional amendments.

Immediately following the Kelo decision,

reports of local and state governments’

using eminent domain for private-to-private

takings died down.

reports of local and state governments’

using eminent domain for private-to-private

takings died down.

Now, a decade after the Kelo case, Paul Larkin,

a senior legal research fellow at The Heritage

Foundation, said he believes municipalities will

begin exercising their eminent domain power

for such condemnations once again now that public pressure has eased some.

a senior legal research fellow at The Heritage

Foundation, said he believes municipalities will

begin exercising their eminent domain power

for such condemnations once again now that public pressure has eased some.

“There have been so many developments in

the law, so many developments in life and so

many developments in politics since [2005] that

it’s fair to say that this issue, which captivated the American public back 10 years ago when the

Kelo decision was decided, now has dropped

precipitously in the ordinal ranking of important

issues,” Larkin said in an interview with The

Daily Signal. “So it would surprise me for cities

and states not to start to do this again.”

the law, so many developments in life and so

many developments in politics since [2005] that

it’s fair to say that this issue, which captivated the American public back 10 years ago when the

Kelo decision was decided, now has dropped

precipitously in the ordinal ranking of important

issues,” Larkin said in an interview with The

Daily Signal. “So it would surprise me for cities

and states not to start to do this again.”

In the Kholghys’ case, the city voted to

use eminent domain to transfer their privately

owned property to another private party, who

would then redevelop the land and build the

restaurants and entertainment for Glendale 180.

use eminent domain to transfer their privately

owned property to another private party, who

would then redevelop the land and build the

restaurants and entertainment for Glendale 180.

Prior to approving the use of eminent domain

to condemn the Kholghys’ property, the city

conducted a study in 2013 to determine

whether the area is “blighted.”

to condemn the Kholghys’ property, the city

conducted a study in 2013 to determine

whether the area is “blighted.”

According to the survey, a “blighted area”

is one that “substantially impairs or arrests

the sound growth of the municipality, retards

the provision of housing accommodations,

or constitutes an economic or social liability,

and is a menace to the public health, safety,

morals or welfare.”

is one that “substantially impairs or arrests

the sound growth of the municipality, retards

the provision of housing accommodations,

or constitutes an economic or social liability,

and is a menace to the public health, safety,

morals or welfare.”

Additionally, for an area to be deemed

“blighted,” it must satisfy at least four of

12 factors identified by the state, which

range from “slum, deteriorated, or

deteriorating structures” to “unusual

topography or inadequate public improvements

or utilities.”

“blighted,” it must satisfy at least four of

12 factors identified by the state, which

range from “slum, deteriorated, or

deteriorating structures” to “unusual

topography or inadequate public improvements

or utilities.”

For a municipality to legally invoke eminent

domain, a property must be deemed “blighted.”

domain, a property must be deemed “blighted.”

After the 2013 study, the city said Authentic

Persian and Oriental Rugs constituted a

“blighted area.”

Persian and Oriental Rugs constituted a

“blighted area.”

“Your business is what gives you sustenance,”

Larkin said. “Business allows you to buy the

house. Business allows you to provide groceries

for the people who live there. The business

allows you to provide a commodity that the

community desires, and it gives you a place

in the community as a respected businessperson.

If they take your business away, they are essentially taking away that part of not simply what gives you sustenance, but also your identity.”

Larkin said. “Business allows you to buy the

house. Business allows you to provide groceries

for the people who live there. The business

allows you to provide a commodity that the

community desires, and it gives you a place

in the community as a respected businessperson.

If they take your business away, they are essentially taking away that part of not simply what gives you sustenance, but also your identity.”

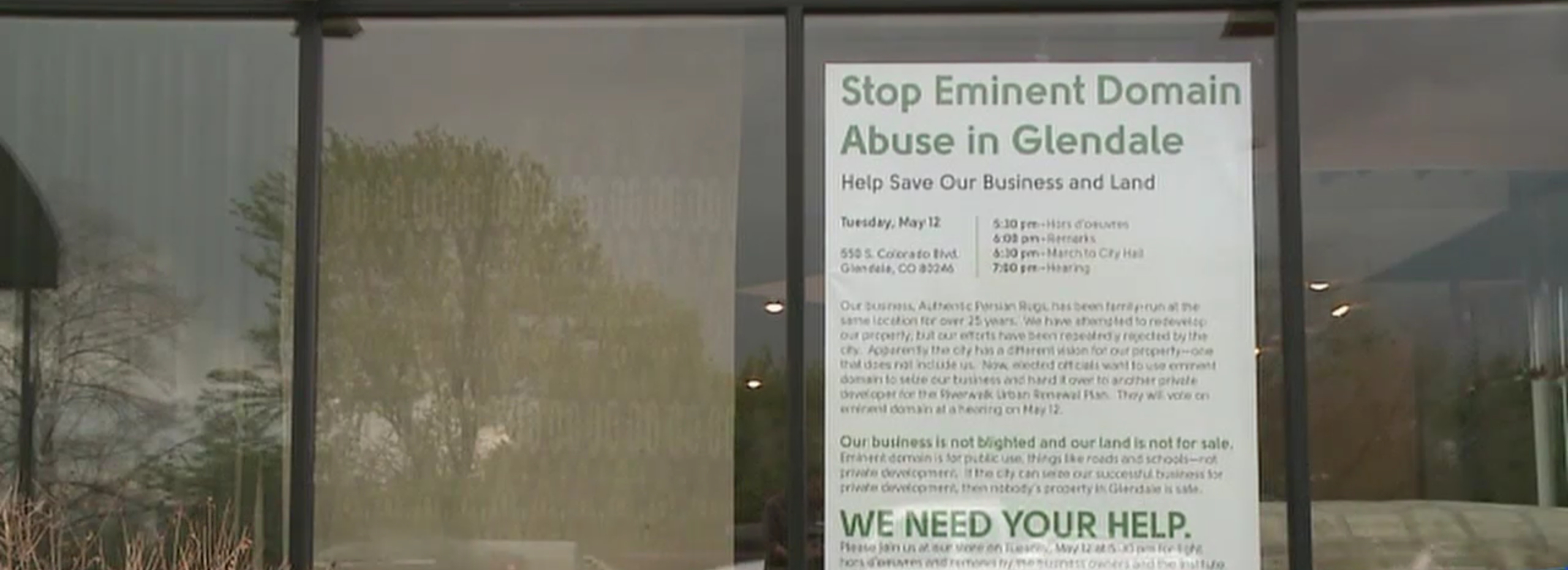

A sign posted in the window at Authentic Persian and

Oriental Rugs calls on customers to protest the use of

eminent domain in Glendale, Colo. (Photo: Screenshot/Fox News)

Oriental Rugs calls on customers to protest the use of

eminent domain in Glendale, Colo. (Photo: Screenshot/Fox News)

‘In Limbo’

Late last month, Glendale offered to buy

the Kholghys’ six acres from the family for

$11 million and gave them several days to

make their final decision.

the Kholghys’ six acres from the family for

$11 million and gave them several days to

make their final decision.

The family turned it down, insisting they

wanted to stay in the same location they

had been for the last 25 years.

wanted to stay in the same location they

had been for the last 25 years.

“The most important thing to us is being here

and having the shop here,” Kholghy said.

and having the shop here,” Kholghy said.

The offer was millions less than a previous

bid the city made in 2012, for $19 million,

which the Kholghys also declined. The city,

Kholghy suspects, was well aware that the

family would decline their July proposal.

bid the city made in 2012, for $19 million,

which the Kholghys also declined. The city,

Kholghy suspects, was well aware that the

family would decline their July proposal.

“If you said no to $19 million, why would

we say yes to $11 million? They knew that,”

Kholghy said. “I think they just said that to

get the media and public pressure off of them.”

we say yes to $11 million? They knew that,”

Kholghy said. “I think they just said that to

get the media and public pressure off of them.”

After the family denied the offer, the city

issued a statement saying they would move

forward with redevelopment without the Kholghys’ property.

issued a statement saying they would move

forward with redevelopment without the Kholghys’ property.

“We were prepared and excited to proceed

either way,” said Dunafon, the Glendale

mayor, in the statement. “But now that the

path forward is clear, things will really kick

into high gear.”

either way,” said Dunafon, the Glendale

mayor, in the statement. “But now that the

path forward is clear, things will really kick

into high gear.”

Linda Cassady, Glendale’s deputy city

manager, told The Daily Signal the city’s

Urban Renewal Authority “doesn’t have

any intention of condemning the property.”

manager, told The Daily Signal the city’s

Urban Renewal Authority “doesn’t have

any intention of condemning the property.”

“If we did that, it would be a really

unfortunate thing for Glendale, and we

really don’t have any intention to do that,” she said.

unfortunate thing for Glendale, and we

really don’t have any intention to do that,” she said.

Kholghy, though, isn’t convinced.

The city has said they won’t use eminent

domain for the Glendale 180 project and

won’t remove the property’s “blighted”

designation, which is legally required to

use eminent domain.

domain for the Glendale 180 project and

won’t remove the property’s “blighted”

designation, which is legally required to

use eminent domain.

“They say, ‘We will not use condemnation

for this project,’” she said. “You will use it

for another project. They leave themselves

open to do what they want at any time.”

for this project,’” she said. “You will use it

for another project. They leave themselves

open to do what they want at any time.”

When asked if the city will re-examine whether

the area is blighted, Cassady said the onus

is on the Kholghys to “cure the blight.”

the area is blighted, Cassady said the onus

is on the Kholghys to “cure the blight.”

Larkin says the Kholghys are right to be skeptical.

“From what I know, everything the city has

done is fully consistent with an effort to be

able to argue in court, were they to take

that property, that they have acted with

entirely benevolent motives of protecting

the property, by advancing the community’s

welfare,” he said.

done is fully consistent with an effort to be

able to argue in court, were they to take

that property, that they have acted with

entirely benevolent motives of protecting

the property, by advancing the community’s

welfare,” he said.

“I don’t think these people are out of the

woods yet,” Larkin continued. “After all,

unless and until the city quite affirmatively

says ‘we will not take your property,’ they

can always walk back from anything they’ve

said before. Even more so, even if they

were to say ‘we will not take your property,’

that doesn’t prohibit other political officials

from changing their mind in the future.’

woods yet,” Larkin continued. “After all,

unless and until the city quite affirmatively

says ‘we will not take your property,’ they

can always walk back from anything they’ve

said before. Even more so, even if they

were to say ‘we will not take your property,’

that doesn’t prohibit other political officials

from changing their mind in the future.’

Kholghy said she just wants to know her

property will be safe from condemnation.

property will be safe from condemnation.

“We don’t want to fight. We don’t want to

be in limbo,” Kholghy said. “You want to

go on with your life. You want to know

what to plan for. Life is hard as it is

without thinking what’s going to happen

in the next day or so.”

be in limbo,” Kholghy said. “You want to

go on with your life. You want to know

what to plan for. Life is hard as it is

without thinking what’s going to happen

in the next day or so.”

No comments:

Post a Comment

Thanks for commenting. Your comments are needed for helping to improve the discussion.