This French City

Knows Le Pen Well

and Sees Her Getting Stronger

Mainstream parties are struggling to maintain voters’ support in the regional capital of Perpignan.

National Front supporters applaud during a local campaign event in Thuir, on the outskirts of Perpignan.

Photographer: Balint Porneczi/Bloomberg

About a hundred expectant white people are packed into a drab, neon-lit hall in southwestern France. Big tricolor flags hang from the walls and above the stage, a navy-blue poster carries the election slogan of the candidate who is promising to address their frustrations: “In the name of the people — Marine — President.”

Marine Le Pen’s

potent mix of old-school left-wing economics and diatribes against immigrants

resonates in this part of the country — and has brought the National Front closer

than ever before to taking power in France. While the Parisian elite is detached from the day-to-day battle with nationalism, the ruling class in the regional capital of Perpignan has been battling to keep its voters away from extremists for decades.

“The Front is spreading,” Mayor Jean-Marc Pujol said in an interview. “There are

districts in the north of Perpignan which used to be communist and now they

are voting for the Front because they worry about immigration.”

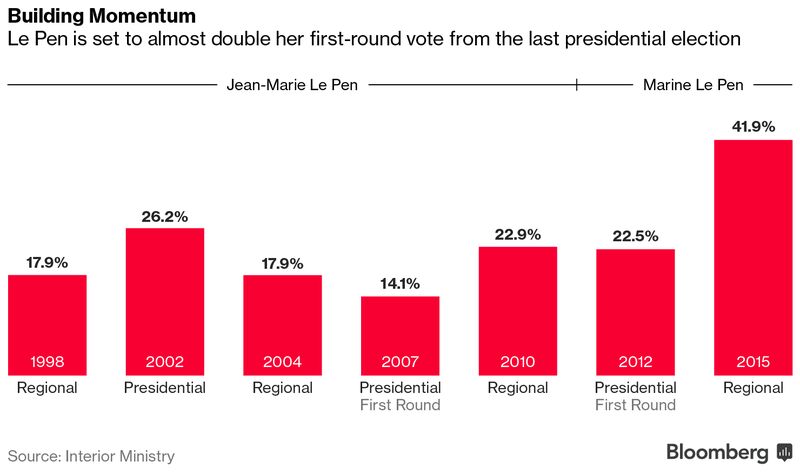

Le Pen is likely to enter the presidential runoff on May 7 as the outsider to be

France’s next leader, but the steady build up of her support is testing the safeguards that have kept extremists from power in the Fifth Republic for almost 60 years.

Pujol predicts that French voters will unite around a mainstream candidate in the presidential runoff on May 7 to prevent the Front from winning power, just as

they did in 2002, in the 2015 regional elections and in his own battle for Perpignan

city hall in 2014. But each time the establishment parties cooperate to keep the

populists out, they feed the narrative of an elitist plot against the people, and

more support shifts to Le Pen.

Jean-Marc Pujol, mayor of Perpignan, in his office.

Photographer: Balint Porneczi/Bloomberg

“Only Le Pen will close the borders so we don’t get foreigners coming in,” Rosy Lamiel, a 59-year-old laundress at a retirement home, said on the sidelines of the National Front rally in the small town of Thuir on the outskirts of the city. “The other parties have let the city go to the dogs.”

In 2014, National Front candidate Louis Aliot led the first round of voting in Perpignan with 34 percent — making it the only large city in France where the Front came top. In the first round of the presidential vote on April 23, Le Pen could get as much as 40 percent, according to Pujol, 67. Pujol only won the runoff against Aliot, who is also Le Pen’s partner, after the Socialist candidate withdrew, maximizing the chances of keeping the Front out.

The Perpignan skyline.

Photographer: Balint Porneczi/Bloomberg

With the worst unemployment rate in France and high levels of immigration, the region of farms and vineyards between the Spanish border and the Mediterranean Sea has proved to be fertile ground for the Front. Perpignan has been left on the sidelines as planemaker Airbus Group SE boosted neighboring Toulouse and most tourists head further east along the coast. Close to 30 percent of locals live below the poverty level, according to national statistics institute Insee.

Throughout its years as a marginal force in French politics, the party enjoyed support among the so-called pieds-noirs — French people who left Algeria after independence in 1962 — and the region’s economic problems have broadened the appeal of Le Pen’s radical plans.

“I back Le Pen because she warned us about the European Union ages ago. I used to believe in the EU and the euro but they’ve ruined us,” 45-year-old winemaker Georges Puig said at the rally. “We’ve been hit by unfair competition.”

The Front’s national proposals to bar immigrants, protect French workers from foreign competition, and crack down on crime are winning over voters like Puig. On a local level it plans to give French people priority for housing or welfare benefits, while condemning the entire ruling class.

“Perpignan brings together all the problems for which the Front has a diagnosis and a cure,” Alexandre Bolo, 30, a National Front official on the city council and parliamentary attache to Aliot, said in an interview. “A migratory invasion, the impoverishment of shops closing and young people forced to leave to find jobs, and a complete lack of dynamism from the powers that be.”

To fend off the nationalists, Mayor Pujol is opening up city-hall branch offices and social centers in the city’s more deprived districts to engage with citizens while beefing up security with more police and CCTV cameras.

The next stage is an initiative to revive the medieval St. Jacques area where a crane towers above the jumble of narrow alleys inhabited mainly by north Africans and Roma. Workmen there are fitting out Perpignan University’s new law faculty where 500 students will attend classes from this fall, moving from the school’s base on the edge of the city.

“We’re bringing one of Europe’s oldest universities back to one of France’s poorest neighborhoods,” said deputy-mayor Olivier Amiel, 38, in charge of urban redevelopment.

Amiel insists that it’s concrete projects to change the lives of local communities that will stop the populists rather than hand-wringing at their sometimes unpalatable views.

“There’s no point in demonizing the Front because so many people vote for it,” he said.

Left: A campaign poster of Marine Le Pen sits on display during a campaign event in Thuir. Right: Pedestrians pass the under-construction university building in the St. Jacques district.

Photographer: Balint Porneczi/Bloomberg

Amid the derelict buildings of St. Jacques where the city reckons some 80 percent of people are out of work, local shopkeepers are looking forward to the university’s arrival.

“It’s a success for the city, and a defeat for the National Front,” said Moroccan-born Aziz Sebaoui, 45, who runs a nearby cafe and heads the local shopkeepers’ association. “We’re working to welcome the students with open arms, we’ll do student prices in the shops near the faculty.”

Longer-term success is not so sure though. Perpignan ultimately needs new jobs if the mayor’s efforts to knit together the city’s different communities are to succeed, and he’s betting on initiatives like the Tecnosud business park south of the city, which combines France’s only school for engineers in the renewable-energy industry alongside businesses working in new energy technology.

“Growth is the only card with which we can beat the Front,” said Andre Joffre, 62-year-old chief executive officer of solar energy firm Tecsol who is backing the independent Emmanuel Macron for president.

While this year’s election may come too soon for Le Pen and the Front, it may nevertheless mark another step in its emergence. Le Pen has eroded the stigma of racist and anti-semitism that once placed a limit on the party’s support and polls show that almost half the electorate is now prepared to consider voting for her.

“The glass ceiling no longer exists,” Pujol said. “We don’t have the dad Jean-Marie scaring everyone. It’s telling that people call his daughter simply ‘Marine.’ They feel close to her.”

This is the second in a series of stories on French populism. Click here to read Gregory Viscusi’s report from Saint-Nazaire.

Photographs by Balint Porneczi/Bloomberg. Graphics by Samuel Dodge

No comments:

Post a Comment

Thanks for commenting. Your comments are needed for helping to improve the discussion.