During a visit to Washington in April 2018, French President Emmanuel Macron's main goal seemed to be convincing US President Donald Trump not to withdraw from the Iran nuclear deal. He tried seduction, hugging Trump incessantly, before turning to arrogance, saying in a speech before Congress: "France will not leave the Iranian nuclear agreement because we signed it. Your President and your country will have to face their responsibilities." (Photo by Alex Wong/Getty Images)

|

On August 25, in Biarritz, France, the leaders of the Group of Seven (G7)

reunited to discuss world problems. The situation in the Middle East was not on the agenda. French President Emmanuel Macron, the organizer of the summit this year, was about to force it in.

He had decided to

invite to the summit Iran's foreign minister, Mohammad Javad Zarif. Macron did not warn his guests of Zarif's attendance until the last minute. His goal, it seems, was to bring about a meeting between the Iranian minister and US President Donald J. Trump. President Trump declined. Zarif had an informal

conversation with Macron and some French ministers, then flew back to Tehran. But Macron did not give up. At a press conference the next day, he publicly

asked President Trump to meet Iranian leaders as soon as possible.

Trump, in answering a journalist's question on the possibility of such a meeting, politely

answered that such a meeting was possible, but only "if the circumstances were correct." The Iranian regime answered that first, the United States would have to

remove all sanctions. The Trump administration did not bother to reply.

Macron then

invited to Paris an Iranian delegation led by the deputy foreign minister of Iran, Abbas Araghchi "to try to define a common position to France and Iran." On September 3, the day after the delegation's departure, France

reportedly proposed offering Iran a $15 billion line of credit. In response, Brian Hook, the United States Special Representative for Iran

said on September 4, "We can't make it any more clear that we are committed to this campaign of maximum pressure and we are not looking to grant any exceptions or waivers." This statement meant that the French proposal to the United States was rejected.

The same day, Iranian President Hassan Rouhani

announced that Iran would speed up its uranium enrichment. He did not mention Macron's gambit.

This announcement apparently did not discourage Macron.

The Iran nuclear deal, known as the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA), reached between Iran and China, France, Russia, the UK, the US and Germany on July 14, 2015, but

never signed by Iran -

allowed the Islamic Republic to dispose of $150 billion that had been frozen in foreign banks. French leaders, evidently recognizing an economic opportunity, invited Rouhani to Paris.

When Macron's predecessor, President François Hollande, welcomed Rouhani in January 2016, he expansively

announced that old disputes had to be discarded and that it was time to open a "new chapter in relations between the two countries." Agreements were signed; Rouhani said that Iran "fights terrorism", and Hollande meekly bowed his head.

One of the reasons the French government Donald Trump's election as bad news is that Trump indicated in 2015 that he

considered the Iran nuclear deal to be a bad agreement from which he wished to withdraw.

When Trump was later elected president, it appears that saving the deal became Macron's highest priority.

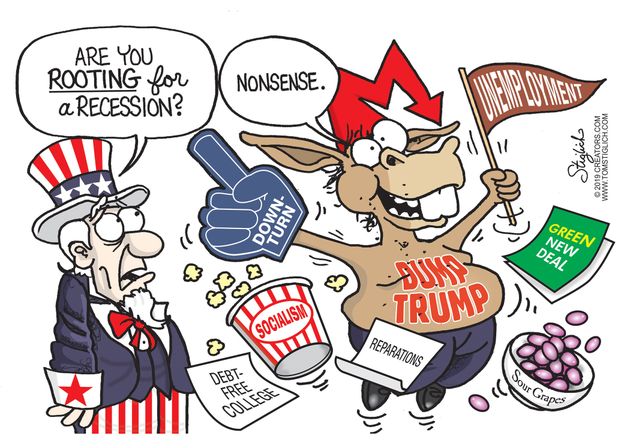

During a visit to Washington in April 2018, Macron's main goal seemed to be convincing Trump to change his mind. He tried seduction,

hugging Trump incessantly. He tried arrogance, announcing in a

speech before Congress:

"France will not leave the Iranian nuclear agreement because we signed it. Your President and your country will have to face their responsibilities."

After Trump

announced on May 8, 2018 that the US would be abandoning the nuclear deal, Macron apparently panicked and asked for an emergency meeting of European leaders. The European Union

asked French and European companies to defy Trump, but ultimately, fearing American sanctions, some European companies

stopped doing business in Iran.

France and Germany then tried to set up a mechanism to help companies bypass America's decision and continue doing business with Iran. A system of evading US sanctions on Iran,

Instex (Instrument in Support of Trade Exchanges), was formally introduced in early 2019, but is still

not operational. No major European decision-maker, it seems, wants to take the risk of using it and having a problem with the United States.

On September 8, days after Rouhani's statement on speeding up Iran's uranium enrichment, French Foreign Minister Jean Yves Le Drian

summarized the French position. He said that Iran was making "bad decisions," but that France would try to help and "keep the dialogue going." He added, incorrectly but unflappably, that Iran had scrupulously respected the nuclear agreement until the moment the United States "sat on the deal." He further added, bewilderingly, that Iran had been "deprived of the benefits" it could expect from the deal -- referring, it seems, to the opportunity soon to engage in legitimate unlimited nuclear weapons development -- and how it was now necessary "to avoid the risk of regional destabilization." He did not specify which region. He threw in the criticism that "America prevents non-American companies from taking their decisions freely."

Macron and the French government know perfectly well that the nuclear deal was

flawed, that it did not prevent the Iranian regime from pursuing its bellicose activities. Macron and the French government also know that Iran repeatedly

violated the deal. They also know that Israel's Mossad intelligence services seized thousands of damning documents in Tehran. They were public information,

disclosed by Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu on April 30, 2018. French officials, however, continued to speak as if they knew nothing. They lied.

Sadly, they still persist in claiming that President Trump arbitrarily withdrew from the

unsigned deal, and they pretend not to know what Trump

said when he announced his decision:

"The Iranian regime is the leading state sponsor of terror. It exports dangerous missiles, fuels conflicts across the Middle East and supports terrorists, proxies and militias such as Hezbollah, Hamas, the Taliban and Al Qaeda.

"Over the years, Iran and its proxies have bombed American embassies and military installations, murdered hundreds of American service members and kidnapped, imprisoned and tortured American citizens. The Iranian regime has funded its long reign of chaos and terror by plundering the wealth of its own people...

"the deal allowed Iran to continue enriching uranium and over time reach the brink of a nuclear breakout. The deal lifted crippling economic sanctions on Iran, in exchange for very weak limits on the regime's nuclear activity and no limits at all on its other malign behavior..."

French officials also falsely claimed that Iran had not "benefited" from the deal. Iran, however, instead of making investments with foreign companies, Iran simply used the bulk of the $150 billion of unfrozen funds and credits to provide Islamic terrorist organizations with up billions to sow

mayhem and death throughout the

Middle East, attack the assets of the

US and the

UK, and knock out half of

Saudi Arabia's oil production -- representing 5% of the daily global oil supply.

French officials speak of "regional destabilization" as if they did not see that Iran has already profoundly destabilized

Syria,

Lebanon,

Yemen and the

Gaza Strip.

French officials also disingenuously claim the need to defend free trade and free enterprise -- an excuse that is a transparent subterfuge to help a criminal regime.

They also never mention the innumerable

human rights violations committed by the regime, and the despair and

misery of the Iranian people. Nor do they ever speak of the harsh

anti-Semitic rhetoric disseminated by most regime leaders and the incessant calls for the genocidal

destruction of Israel by Iran's leader, Ayatollah Ali Khamenei.

The French officials act and speak as if the Iranian regime was totally honorable, and as if they did not discern the obvious: that the Iranian regime has

destructive goals. The nuclear deal did not divert the regime from its goal of building

nuclear weapons. The deal, in fact, floated the regime toward precisely that end. The American strategy of applying maximum pressure through economic sanctions seems the only non-military way to

pressure this regime to change course.

In light of France's history of appeasing hostile regimes, France's attitude toward the Iranian regime is not really surprising.

In the past few decades, France tried several times to give priority to its immediate financial interests, even if it increased the danger to others and even ultimately to themselves. In 2001-2002, when France signed oil deals with Iraq,

documents show that the French opposition to toppling Saddam Hussein was essentially based on a desire to save the oil deals. Three decades earlier, on November 18, 1975, after France had

signed a nuclear cooperation agreement with Iraq, then Iraqi dictator Saddam Hussein

called the agreement "the first concrete step towards the production of the Arab atomic weapon." Had Israel not

destroyed the nuclear reactor at Osirak on June 7, 1981, Iraq would almost certainly have been able to acquire nuclear weapons. The attempt of France today to prioritize its financial interests in spite of the Iranian regime's malign activities, is simply doing more of the same.

French leaders have often criticized -- or even attempted to obstruct -- the United States whenever it was confronted by enemies. On September 1, 1966, General Charles de Gaulle delivered a

speech in Phnom Penh, Cambodia, harshly criticizing "American imperialism" in Vietnam. When US President Ronald Reagan described the Soviet Union as an "evil empire," the French Ministry of Foreign Affairs

expressed "reservations" about America's "risky hawkish attitude." When US President George Walker Bush designated North Korea, Iraq and Iran as the "axis of evil," French President Jacques Chirac

spoke of his "fright".

French leaders have, in addition, rarely taken into account the fate of populations in countries with which potentially lucrative relations could be made. They never paid attention to the anti-Semitic speeches and

calls for the destruction of Israel that erupted from leaders of the Muslim world. They have generally overlooked declarations of war from Israel's enemies. In 1967, shortly before the outbreak of the Six-Day War, General de Gaulle

decided on an arms embargo against Israel. In 1973, during the Yom Kippur War, when Egypt and Syria attacked Israel, French Foreign Minister Michel Jobert

said that the "Arabs wanted to return home" and added that that it was "not necessarily an aggression." The indifference of French leaders toward Iran's threats towards Israel is all of a piece with well-established French political traditions.

France is not the only European country behaving this way toward the Iranian regime. When Angela Merkel realized that Macron had failed to convince Trump to stay in the nuclear deal, she

went to Washington and

she attempted to influence the president. To this day, Germany continues to endorse France's positions regarding Iran.

Instex was born out of cooperation between the France and Germany. German Foreign Minister Heiko Maas even

went to Tehran to explain to the Iranian government how the trade instrument would work.

The European Union, as well,

supports France's position.

Macron, in short, has

done as much or

more than any other European country to favor the Iranian regime -- more than Germany, and even more than the European Union itself.

He could have chosen to act as a reliable ally of the United States, but the choice he made was a different.

In a

speech on October 31, 2017 before the Council of Europe in Strasbourg, Macron said that "making human rights prevail is a fight, even for countries like France." It is sometimes difficult to see how Macron tries to make human rights prevail at all.

Political analyst Daniel Krygier

wrote recently that "President Trump does not offer anything without getting something in return." Even if Trump were to decide to meet Rouhani, and even if it were a useless meeting, Trump would address it from a position of strength, and one hopes, without having conceded to anything.

On September 14, just a few days after former National Security Advisor Ambassador John R. Bolton was comfortably disappeared from the administration, Iran inflicted major

damage on a massive oil processing facility in Saudi Arabia,

disrupting half of Saudi Arabia's oil production and 5% of the world's daily oil supply. While Iran-backed Houthi insurgents, currently fighting a war with Saudi forces in Yemen, claimed responsibility, the US

blames Iran.

Secretary of State Mike Pompeo

sent a tweet saying that "there is no evidence the attack came from Yemen" and added:

"Tehran is behind nearly 100 attacks on Saudi Arabia while Rouhani and Zarif pretend to engage in diplomacy. Amid all the calls for de-escalation, Iran has now launched an unprecedented attack on the world's energy supply...

"We call on all nations to publicly and unequivocally condemn Iran's attacks. The United States will work with our partners and allies to ensure that energy markets remain well supplied and Iran is held accountable for its aggression."

Trump might, nevertheless, meet with Rouhani in New York.

The French government issued a

statement saying that the attack on the Saudi oil processing facility could "aggravate tensions and the risks of conflict in the region". Iran was not even mentioned.

French Foreign Minister Jean-Yves Le Drian

said:

"Up to now France doesn't have proof permitting it to say that these drones came from such and such a place, and I don't know if anyone has proof.... We need a strategy of de-escalation for the area, and any move that goes against this de-escalation would be a bad move for the situation in the region."

"The attack," a French diplomatic source

added, "does not help what we are trying to do."

Dr. Guy Millière, a professor at the University of Paris, is the author of 27 books on France and Europe.