12 Women Who Ran For President Before Hillary

JONATHAN ERNST / REUTERS

“Don’t know much about history...”That single lyric, smoothly sung by Sam Cooke, has been rolling around in my head since June 7th, when Hillary Rodham Clinton became the first woman in our 240-year history to lead the presidential ticket for a major political party.

While I remember 2008—I voted in 2008—and I remember Bill Clinton’s presidency—though it was in my childhood—I feel now like I don’t know much about history, at least not the gender-inclusive history that’s unfolding before my millennial eyes. What I know of Hillary’s journey I know only in the context of my lifetime, and it’s easy to feel that Hillary has accomplished much of what she’s accomplished alone. But the reality is other women ran for both president and vice president before 2008, all aiding in the realization of Clinton’s 2016 “clinch.”

It is heartbreaking for me to admit that I’d never heard of any of these other women until very recently. I’m too young to remember Geraldine Ferraro as Walter Mondale’s 1984 running mate, and too old to have had my public school education include lessons in the impact Clinton and Sarah Palin had on the 2008 election (I’m assuming, and hoping, this is mentioned in schools now, though I don’t know if it is). History class, for me, was the retelling of our already commonly-told stories of famous straight white men. No one taught me an African American woman ran for president in 1972. No one taught me the first woman to run for president did so in 1872, before women could legally vote. No one taught me these stories of female determination and ambition, though they happened—they were out there for the teaching.

These are the histories that need to be remembered. As the famous adage goes: If you don’t know your history, you’re doomed to repeat it. By keeping these women from our text books and lesson plans (and even from common public knowledge), we’ve allowed the sexism they faced in the past to persist as if it never happed, as if every time is the first time. As a country we are stuck in a cycle of rediscovering our misogyny, but never escaping it, because we have yet to fully historically acknowledge it.

In 2016 it’s time to learn the names of the woman listed below and study the impact their lives had on the United States. It’s time to learn our history.

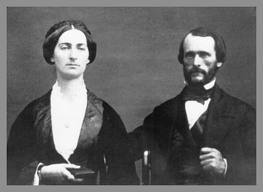

Jessie Benton Fremont

While Jessie Benton Freemont did not run for president (her husband did in 1856, as the first-ever nominee for the Republican Party), she’s included here because many felt at the time that—like Hillary—she could have been an even stronger candidate than her husband if only she were to run instead.

Fremont was a writer and political activist who was publically opposed to slavery. She campaigned for her husband and rallied such massive support that the campaign slogan “Fremont and Jessie Too” was born. It parallels Bill Clinton’s 1992 statement that a vote for him would mean the American public would get “two for the price of one,” referring to Hillary’s impressive political qualifications and accomplishments.

Two-for-one comments were also made regarding John and Elizabeth Edwards and Barack and Michelle Obama—additional couples featuring qualified, accomplished, and socially involved wives, both of whom, like Hillary, graduated from law school.

Victoria Woodhull (1872)

Victoria Woodhull was the first woman to run for President of the United States as the candidate for the Equal Rights Party. She was a suffragette, a champion for equal rights (as her party’s name suggests), and an advocate for “free love,” which she meant as the freedom for people to marry, divorce, and bear children without government interference.

Woodhull’s groundbreaking run for the presidency is even more impressive when its full context is considered: She ran for president in a time when women did not even have the legal right to vote. Woodhull was a pioneering suffragette, and she believed, and publically argued, that women actually already had the legal right to vote under the Privileges and Immunities Clause of the Constitution. She presented this argument before the House Judiciary Committee in 1871, but the Supreme Court ruled against her interpretation of the Constitution. Women who showed up to the polls to vote for any party in the 1872 election were arrested.

Woodhull’s campaign was also revolutionary in its nomination for vice president, electing former slave and abolitionist Frederick Douglass to its ticket (though Douglass never publically acknowledged the nomination). It was the goal of Woodhull and the Equal Rights Party to reunite the causes of women’s equality and racial equality, as a schism between the movements was created two years earlier when the 15th Amendment granted African American men the right to vote but still denied the right to women of every race.

For all her revolutionary acts on behalf of women’s rights, Woodhull had trouble securing the support of even the most revolutionary female thinkers and activists in the country—the women who perhaps should have realized, better than most, what Woodhull’s run for the presidency meant for their own lives and their liberal causes. (It’s, sadly, a familiar tale even today, told by Hillary and her strained—sometimes non-existent—support from female Obama and Bernie loyalists.) The most striking example of women denying support to Woodhull involves suffragette Susan B. Anthony.

Thirteen years before Woodhull’s run for the presidency, in 1859, Elizabeth Cady Stanton, a leading figure of the early women’s rights movement, wrote to Anthony, “When I pass the gate of the celestials and good Peter asks me where I wish to sit, I will say, ‘Anywhere so that I am neither a negro nor a woman. Confer on me, great angel, the glory of White manhood, so that henceforth I may feel unlimited freedom.’” The correspondence between the friends and peers shows their early recognition of the disadvantages women of all races faced in the U.S. However, when it came to the 1872 election, Susan B. Anthony and Elizabeth Cady Stanton did not vote for Woodhull, though both publically applauded Woodhull’s pioneering efforts on behalf of all women. Anthony’s (illegal, and therefore irrelevant) vote was cast for a straight Republican ticket. Woodhull did not receive any electoral votes, and Republican Ulysses S. Grant won the election.

Woodhull tried again to run for president in 1884 and 1892, gaining more traction in ‘92, when she was nominated to be the presidential candidate by the National Woman Suffragists’ Nominating Convention. Marietta Stowe was nominated to Woodhull’s ticket as the Convention’s candidate for vice president. The nominations were more symbolic than anything, unfortunately, as the nominating committee was unauthorized and nothing came of their proposed Woodhull/Stowe ticket.

Belva Ann Lockwood (1884)

While the unofficial Woodhull/Stowe ticket of 1892 may seem like the original version of a possible Clinton/Warren 2016 ticket, Marietta Stowe was actually attached to the Equal Rights Party’s 1884 ticket as the vice presidential candidate to presidential nominee Belva Ann Lockwood. In 1884, Lockwood accomplished something Woodhull couldn’t in ‘72, as she became the first woman to appear as a candidate on official ballots.

Newspapers at the time slung insults at Lockwood that were, sadly, not too different from discriminatory statements made by Fox News talking heads in 2008 against Hillary. She was called “old lady Lockwood” and men were warned her election would bring on a “dangerous” form of “petticoat rule.”

It was reported that Lockwood received approximately 4,000 votes in the election, though she believed this number was significantly lower than the true number of votes cast by her supporters. In 1885 she petitioned Congress to investigate voter fraud committed against her, stating many votes for her were either not counted or thrown in waste baskets for being “false votes,” but nothing came of her petition. She ran again for president in 1888 with less fanfare and success.

Gracie Allen (1940)

Gracie Allen’s campaign for the presidency might have had more in common with Trump’s than Clinton’s. A comedian and film and television star, Gracie rose to fame as one half of the comedy duo Burns and Allen, playing the comic foil to her “straight man” husband George Burns.

Their act was very popular, especially during the Depression, when the American public needed a laugh more than most anything (like, you know, food and work). Tapping into the country’s desire for lightheartedness, Burns and Allen began a series of pranks they played out weekly on their radio show. For their second successful prank, in 1940, they announced Allen would run for President on the Surprise Party ticket:

Ms. ALLEN: George, I’ll let you in on a secret. I’m running for president.

(Soundbite of applause)

Mr. BURNS: You’re running for president?

Ms. ALLEN: Yes.

Mr. BURNS: Gracie, how long has this been going on?

Ms. ALLEN: Well, for 150 years, George Washington started it.

Mr. BURNS: But in the entire history of the United States, there’s never been a woman president.

Ms. ALLEN: Yeah, isn’t that exciting? I’ll be the first one.

Though it was initially a joke, Allen soon garnered a real following hoping to elect her Commander in Chief. Burns and Allen campaigned across the country, preforming their comedy act before Allen delivered humorous stump speeches, full of what would soon be known as “Gracie-isms.” A few favorites were, “Everybody knows a woman is better than a man when it comes to introducing bills into the house,” and, “We ought to be proud of the National Debt, it’s the biggest in the world!”

Over 100,000 people came out to see Allen on her mock campaign trail, and she received an official endorsement from Harvard University at their pick for the presidency. She dropped out of the race before the election, but received thousands of write-in votes on election day, even against political heavyweight (and eventual winner) Franklin Delano Roosevelt.

After the election Allen and Burns wrote a book about the presidential prank titledHow to Become President. In an earnest moment, Allen states, “No matter what people say about them or what they say about each other, candidates are human beings, and we need them.”

Margaret Chase Smith (1964)

Margaret Chase Smith ran for the Republican ticket in 1964 against Barry Goldwater, and became the first woman ever to receive more than one vote at a major party convention. (In fact, she received a whopping 27...out of 1,308.) She lost every primary in the election, but did make positive headlines when she secured 25-percent of the vote in Illinois.

She was the first member of the Senate to oppose Senator Joseph McCarthy for his Communist and Soviet fearmongering (later known as “McCarthyism”), saying, “I don’t want to see the Republican Party ride to a political victory on the Four Horsemen of Calumny—Fear, Ignorance, Bigotry, and Smear.” Her 1950 speech, “Declaration of Conscience,” is well-remembered for her strong and outspoken criticism of McCarthy’s questionable tactics.

Smith’s run for the presidency inspired a young Hilary Clinton, who was initially a supporter of Barry Goldwater, to run for president of her high school class. Like Smith, Hillary lost her ‘64 campaign. Clinton wrote in her memoir that the loss did not surprise her, but “still hurt, especially because one of my opponents told me I was ‘really stupid if I thought a girl could be elected president.’”

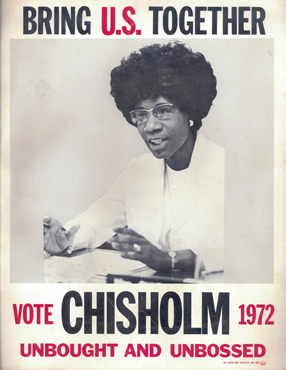

Shirley Chisholm (1972)

Shirley Chisolm was the first black woman elected to Congress in the United States. In 1972 she announced her bid for the presidency under the Democratic Party and took her campaign all the way to the DNC. Like Hillary, Chisolm was a realistic and grounded political thinker who knew exactly what it would take for any person to become president. She said of her own campaign, “You can go to that Convention and you can yell, ‘Women power! Here I come!’ You can yell, ‘Black power! Here I come!’ The only thing those hard-nosed boys are going to understand at that Convention: ‘How many delegates you got?’”

At the Convention in Miami, Hubert Humphrey released his black delegates to vote for Chisholm, which help Chisholm to win 152 votes. While it wasn’t enough to secure the nomination, it ensured that she would address the crowd at the party’s gathering, where George McGovern ultimately received and accepted his place on the party’s ticket.

Chisholm wrote in 1973, in her book The Good Fight, of her run for the presidency, “The United States was said not to be ready to elect a Catholic to the Presidency when Al Smith ran in the 1920’s. But Smith’s nomination may have helped pave the way for the successful campaign John F. Kennedy waged in 1960. Who can tell? What I hope most is that now there will be others who will feel themselves as capable of running for high political office as any wealthy, good-looking white male.”

Chisolm passed away in 2005, just three years before President Obama and Hillary Clinton’s historic run for the Democratic nomination.

Patsy Matsu Takemoto Mink (1972)

In 1965, Patsy Mink became the the first woman elected to Congress for the state of Hawaii, as well as the first elected female of an ethnic minority from any state. Mink ran in the Oregon primary for the 1972 election as an anti-Vietnam War candidate for the Democratic ticket, but received only two-percent of the votes. She dropped out of the race soon after, and went on to support the campaign of Democratic nominee George McGovern (alongside Shirley Chisholm).

Mink was a principal author and sponsor of the Title IX Amendment of the Higher Education Act, which prohibits gender discrimination by federally funded institutions. She also authored and introduced the Early Childhood Education Act and Women’s Education Equality Act.

President George W. Bush renamed the Higher Education Act to the Patsy T. Mink Equal Opportunity in Education Act in 2002. In 2014, President Obama awarded her a posthumous Presidential Medal of Freedom for her lifetime of contributions to the country.

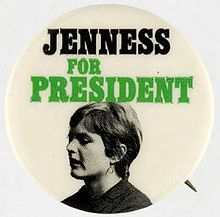

Linda Jenness (1972)

While Chisholm and Mink attempted to top the ticket for a major party in ‘72, Linda Jenness ran for election that same year on the Socialist Workers Party ticket. Her political career was largely focused on challenging laws and constitutional requirements that make it difficult for third parties to become true contenders in presidential elections, including state ballot access laws, requirements for equal media coverage of third-party candidates, and the ability to distribute third-party campaign literature on army bases.

Jenness received over 80,000 votes in the ‘72 election, but her run was doomed from its start, as Jenness was not of the legal age—35—to be elected president. Regardless, she was featured on the ballot in 25 states, and her running mate, communist Evelyn Reed, was written-in on behalf of the Socialist Workers Party in three additional states (Indiana, New York, and Wisconsin). Both women remained loyal to communist and Marxist movements after the ‘72 election.

Geraldine Ferraro (V.P., 1984)

In 1984, Minnesota Senator Walter Mondale made history when he chose New York congresswoman Geraldine Ferraro to be his running mate for vice president. It was the first time a woman’s name appeared as the V.P. candidate on a major party ticket.

While campaigning on both the trail and TV, Ferraro was bombarded with sexist questions like, “Vice president, okay, fine. But do you think you’re equipped to bepresident?” (asked by none other than female TV anchor Barbara Walters) and “Do you think the Soviets might be tempted to take advantage of you simply because you’re a woman,” which was asked of her directly at the ‘84 vice presidential debate. Mondale and Ferraro lost to Regan and Bush by a landslide.

Ferraro supported Clinton in 2008. She told feminist reporter Rebecca Traister in 2009, “I didn’t cry when I voted for myself in 1984, but I went into that booth and I looked at Hillary’s name...I’m beginning to well up now thinking about it. It felt like Susan B. Anthony was standing beside me saying, ‘Pull that lever.’ Which sounds so stupid. But I felt the struggle for women’s rights, and it just smashed me.”

Ferraro passed away in March of 2011, just five years before Clinton’s historic nomination.

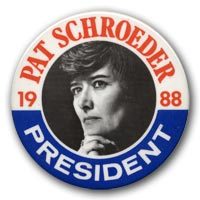

Pat Schroeder (1988)

Pat Schroder was just 47 years old and a representative for Colorado when she gained a Democratic Party following hoping she’d be the first woman nominated to a major party ticket. Schroder was the chair of Gary Hart’s campaign for the presidency, but when he dropped out, his supporters urged her to enter the race herself, which she did, though only briefly.

She’s most remembered for her 1987 press conference announcing her withdrawal from the race, which was called “emotional” in the press. Much like Hillary Clinton’s “dry tears” in 2008, Schroeder was ostracized, and even received hate mail, for speaking sentimentally and allowing her voice to crack. The New York Timesdescribed Schroeder’s withdrawal speech in their same-day coverage:

‘’I could not figure out how to run,’’ she said. And then she paused, overcome by emotion and unable to finish the sentence. Her audience applauded encouragement. She resumed: ‘’I could not figure out how to run and not be separated from those I serve. There must be a way, but I haven’t figured it out yet.’’

Schroder’s own “dry tears” scandal hung over much of her legacy, while nothing was said of any other ‘88 candidates’ wistful goodbyes to their supporters, including the withdrawal speech of candidate Joe Biden, which occurred just one week before Schroder’s.

In the same article detailing her withdrawal, The New York Times wrote of Schroder’s campaign and its ties to feminism:

Two of Mrs. Schroeder’s most serious concerns about becoming a Presidential candidate involved fears that she would be perceived largely as a feminist candidate and, relying on this relatively narrow base, would be unable to make a respectable showing. She said today that although some voters regarded her as ‘’a woman running for President,’’ others still saw her as ‘’the woman’s candidate for President.’’Some Democrats favorable to Mrs. Schroeder’s candidacy had been apprehensive that her campaign might be dominated by strident feminists, insisting on prominence for their issues and hurting rather than improving her prospects.

Sound familiar?

Carol Moseley Braun (2004)

While Shirley Chisholm was the first African-American woman elected to Congress, Carol Moseley Braun was the first elected to the Senate. She represented Illinois and the Democratic Party, and in 2004 she attempted to follow in Chisholm’s footsteps with a run for the Democratic Party’s presidential nomination. Braun failed to gain substantial momentum and struggled with campaign funding, causing her drop out of the race just four days before the Iowa caucuses. Mosley encouraged her supporters to vote for Howard Dean.

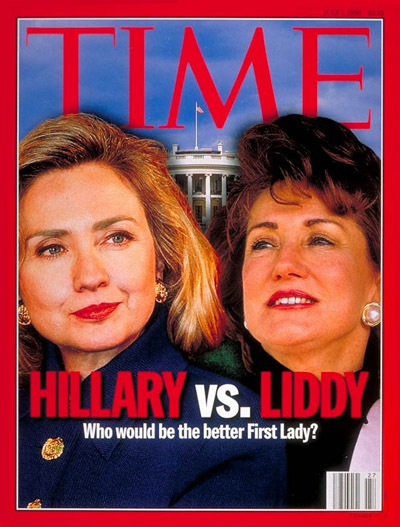

Elizabeth Dole (2000)

Elizabeth Dole’s story reads a lot like a Republican version of Hillary Clinton’s continuing legacy. The wife of U.S. Senate Majority Leader and both presidential and vice presidential nominee Bob Dole, Elizabeth had an impressive political career of her own.

She graduated from Duke University with a degree in political science, then continued her education at Harvard, where she earned both an M.A. in education and a J.D. from Harvard Law. Elizabeth served as the Secretary of Transportation for Ronald Regan and the Secretary of Labor for George H.W. Bush. She later worked for the American Red Cross, and soon after was elected as North Carolina’s first female Senator.

She ran for the Republican nomination in the 2000 presidential election, but dropped out of the race before any primaries took place, mostly due to insufficient campaign funds. Gallop polls placed her in second behind George W. Bush in October of 1999 by only 11 percentage points, with John McCain placing third.

Dole was then on the short list of Bush’s potential vice presidential nominees, and was largely believed to be the frontrunner. Pundits and voters alike were surprised when Bush selected Dick Cheney over Dole (mostly because Cheney was in charge of the V.P. search...draw your own conclusions).

Elizabeth Dole labeled Hillary Clinton the frontrunner for the 2016 election as early as 2013, adding, “ I have to say as far as Hillary is concerned, you know, we can recognize that we’re past the point of a woman being accepted as president because she almost made it last time...Of course, it’s a very personal decision [to run], having been through that myself. It’s something that she will have to decide.”

Thanks, in part, to all the woman who came before her, Hillary decided to go for it.

For additional, in-depth reading on U.S. History and female presidential candidates, pickup Big Girls Don’t Cry by Rebecca Traister, and The Highest Glass Ceiling: Women’s Quest for the American Presidency by Ellen Fitzpatrick.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Thanks for commenting. Your comments are needed for helping to improve the discussion.