Gun Rights Actually Are a Civil Rights Issue

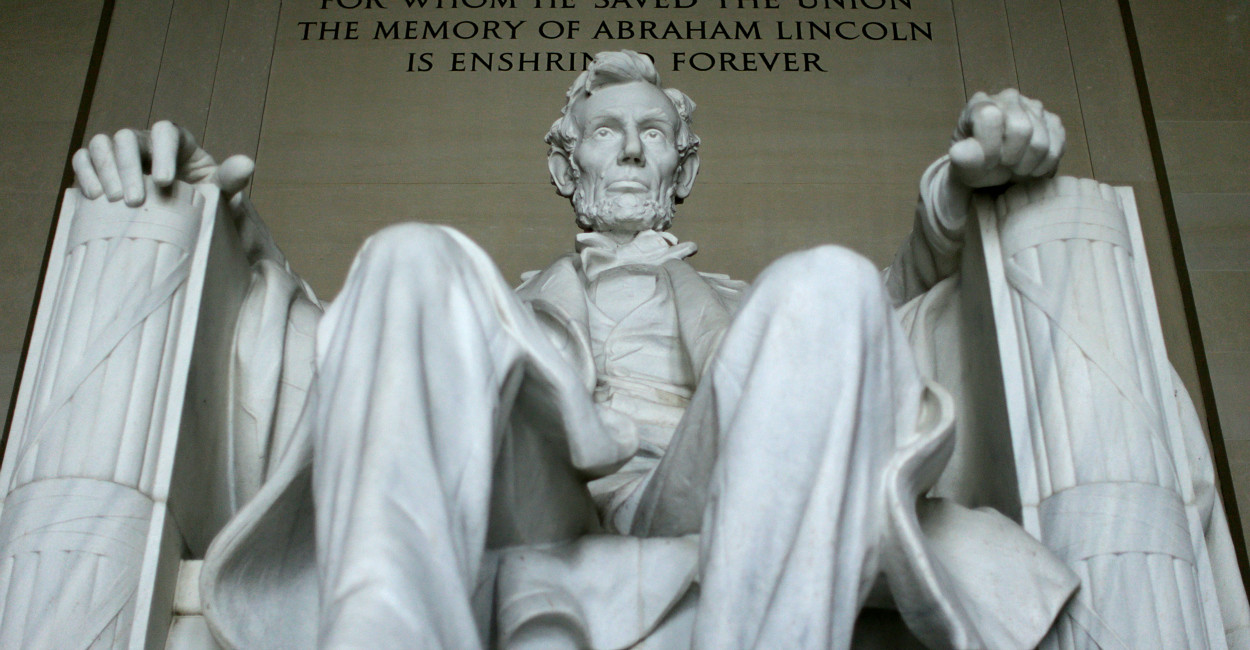

Modern protests demanding more gun control have been likened to the civil rights movement, but civil rights and gun rights often have gone together in American history. (Photo: David Tulis/UPI/Newscom)

It is becoming increasingly fashionable for those who support gun control to compare the post-Parkland, student-driven movement to the civil rights movements of earlier generations.

“Young people said, ‘We will not tolerate what our ancestors have tolerated. We’ve had enough and we’re willing to fight for it and we’re willing to march in the streets for it and, if necessary, die for it,’” TV personality Oprah said in comparing the student marches to civil rights demonstrations.

One writer in The New Yorker wrote of the pro-gun control March for Our Lives protest: “The Parkland students seem to instinctively understand that their fight not only crosses racial and class lines but also exists on a historical continuum, as an extension of the civil-rights movement.”

Another recent article in The Washington Post, headlined “Gun rights are about keeping white men on top,” even tried to connect American gun culture and support for gun rights to racism.

Americans need an alternative to the mainstream media. But this can't be done alone. Find out more >>

However, the author’s historical argument, whether intentionally or not, actually reveals that it is gun control, not gun rights, that generally has been used for the purposes of white supremacy.

Gun rights and civil rights, historically, have gone hand in hand.

In a recent interview on “The View,” former Secretary of State Condoleezza Rice highlighted the importance of preserving the Second Amendment as an individual right, in some cases the last line of defense in protecting life and liberty.

“Let me tell you why I’m a defender of the Second Amendment,” Rice said on the show. “I was a little girl growing up in Birmingham, Alabama, in the late ‘50s, early ‘60s. There was no way that Bull Connor and the Birmingham police were going to protect you.”

“I’m sure if Bull Connor had known where those guns were, he would have rounded them up,” she said. “So I don’t favor some things like gun registration.”

‘The Work of the Abolitionists Is Not Finished’

In the aftermath of the Civil War, a ferocious battle emerged over how to preserve both federalism and the individual rights of citizens in the states.

Gun rights, in some cases, were the only safeguard of liberty and personal safety.

Some of the first states to pass highly restrictive gun control legislation were, in fact, in the Reconstruction-era South. They implemented so-called “black codes” to restrict the rights of former slaves, including the right to bear arms.

One 1866 Alabama law baldly stated that “it shall not be lawful for any freedman, mulatto, or free person of color in this state, to own firearms, or carry about his person a pistol or other deadly weapon.”

The law also made it illegal “to sell, give, or lend firearms or ammunition of any description whatever, to any freedman, free negro, or mulatto.”

Famed abolitionist Frederick Douglass warned about these abuses and said“the work of the abolitionists is not finished” until the Second Amendment and others rights could be protected.

This provoked a federal response, according to historian Stephen P. Halbrook. Congress passed the Freedmen’s Bureau Act of July 1866, which guaranteed to other men “any of the civil rights or immunities belonging to white persons, including the right to … inherit, purchase, lease, sell, hold, and convey real and personal property, and to have full and equal benefit of all laws and proceedings for the security of person and estate, including the constitutional right of bearing arms.”

President Andrew Johnson vetoed this legislation, but he was overridden by Congress.

These battles over the protection of individual rights culminated in the passage of the 14th Amendment.

The 14th Amendment was designed to prevent states from violating the Bill of Rights, which at the time applied only to the federal government.

However, even after the passage of the 14th Amendment, racial conflict and battles over gun rights continued for generations.

As Rice explained, individual firearm ownership was often the only protection black Americans had under some legal authorities that did little to protect them.

As Ida B. Wells, one of the founders of the NAACP and an early civil rights leader, wrote in 1892, a year in which an extraordinary number of brutal lynchings took place: “The only times an Afro-American who was assaulted got away has been when he had a gun and used it in self-defense.”

“The lesson this teaches and which every Afro-American should ponder well,” Wells continued, “is that a Winchester rifle should have a place of honor in every black home, and it should be used for that protection which the law refuses to give.”

An Inalienable Right

Supreme Court Justice Clarence Thomas noted this history in his concurring opinion in the Chicago v. McDonald case in which the court ruled that Otis McDonald, a black Army veteran, had been deprived of his Second Amendment rights by the city of Chicago.

Thomas wrote about how the infamous Dred Scott decision before the Civil War was meant to strip black Americans of citizenship and “the constitutionally enumerated rights of ‘the full liberty of speech’ and the right ‘to keep and carry arms.’”

After the war, former Confederate states attempted to curtail firearm ownership for black citizens, and mob and militia violence against those citizens often went unchecked by local authorities.

“Without federal enforcement of the inalienable right to keep and bear arms, these militias and mobs were tragically successful in waging a campaign of terror against the very people the 14th Amendment had just made citizens,” Thomas wrote.

Thomas concluded that in the opinion of the Founders and authors of the 14th Amendment, “the right to keep and bear arms was essential to the preservation of liberty.”

As Thomas, Douglass, Rice, and others so clearly articulated, gun rights—not gun control—have been an essential buttress to civil rights.

this month, the 13th Amendment officially

was ratified, and with it, slavery finally

was abolished in America. The New York

World hailed it as “one of the most important

reforms ever accomplished by voluntary

human agency.”

“takes out of politics, and consigns to

history, an institution incongruous to our

political system, inconsistent with

justice and repugnant to the humane

sentiments fostered by Christian

civilization.”

—which states that “[n]either slavery

nor involuntary servitude, except as a

punishment for crime whereof the party

shall have been duly convicted, shall

exist within the United States, or any

place subject to their jurisdiction”—the

central contradiction at the heart of the

Founding was resolved.

be free and equal, race-based chattel

slavery would be no more in the United States.

about the status of slavery under the

original Constitution. Textbooks and

history books routinely dismiss the

Constitution as racist and pro-slavery.

The New York Times, among others,

continues to casually assert that the

Constitution affirmed African-Americans

to be worth only three-fifths of a human being.

opposed to racism unwittingly agree with

Chief Justice Roger Taney’s claim in Dred Scott v.

Sandford (1857) that the Founders’ Constitution

regarded blacks as “so far inferior that they

had no rights which the white man was

bound to respect, and that the negro

might justly and lawfully be reduced to

slavery for his benefit.” In this view, the

worst Supreme Court case decision in

American history was actually correctly

decided.

for the health of our republic. They teach

citizens to despise their founding charter

and to be ashamed of their country’s origins.

They make the Constitution an object of

contempt rather than reverence. And they

foster alienation and resentment among

African-American citizens by excluding them

from our Constitution.

If we turn to the actual text of the Constitution

and the debates that gave rise to it, a

different picture emerges. The case for

a racist, pro-slavery Constitution

collapses under closer scrutiny.

racist suffers from one fatal flaw: the

concept of race does not exist in the

Constitution. Nowhere in the Constitution

—or in the Declaration of Independence,

for that matter—are human beings

classified according to race, skin color,

or ethnicity (nor, one should add, sex,

religion, or any other of the left’s

favored groupings). Our founding

principles are colorblind (although

our history, regrettably, has not been).

citizens, persons, other persons (a

euphemism for slaves) and Indians

not taxed (in which case, it is their

tax-exempt status, and not their skin

color, that matters). The first

references to “race” and “color”

occur in the 15th Amendment’s

guarantee of the right to vote, ratified in 1870.

a canal against the ruins of Richmond, Va., after Union troops

took the city on April 3, 1865. (Photo: Everett Collection/Newscom)

more nonsense has been written than any

other clause, does not declare that a black

person is worth 60 percent of a white person.

It says that for purposes of determining the

number of representatives for each state in

the House (and direct taxes), the government

would count only three-fifths of the slaves,

and not all of them, as the Southern states,

who wanted to gain more seats, had insisted.

The 60,000 or so free blacks in the North and

the South were counted on par with whites.

Constitution also does not say that only

white males who owned property could vote.

The Constitution defers to the states to

determine who shall be eligible to vote

(Article I, Section 2, Clause 1). It is a little

known fact of American history that black

citizens were voting in perhaps as many

as 10 states at the time of the founding

(the precise number is unclear, but only

Georgia, South Carolina, and Virginia

explicitly restricted suffrage to whites).

blacks or whites, but it also doesn’t

mention slaves or slavery. Throughout

the document, slaves are referred to as

persons to underscore their humanity.

As James Madison remarked during the

constitutional convention, it was “wrong

to admit in the Constitution the idea that

there could be property in men.”

three different formulations: “other persons”

(Article I, Section 2, Clause 3), “such

persons as any of the states now existing

shall think proper to admit” (Article I,

Section 9, Clause 1), and a “person

held to service or labor in one state, under

the laws thereof” (Article IV, Section 2, Clause 3).

have done much to improve the lot of

slaves, they are important, as they

denied constitutional legitimacy to the

institution of slavery. The practice

remained legal, but slaveholders could

not invoke the supreme law of the land

to defend its legitimacy. These formulations

make clear that slavery is a state institution

that is tolerated—but not sanctioned—

by the national government and the

Constitution.

visitor from a foreign land would simply

have no way of knowing that race-based

slavery existed in America. As Abraham

Lincoln would later explain:

Frederick Douglass did in the lead-up to the

Civil War, that none of the clauses of the

Constitution should be interpreted as

applying to slaves. The “language of the

law must be construed strictly in favor

of justice and liberty,” he argued.

explicitly recognize slavery and does

not therefore admit that slaves were

property, all the protections it affords

to persons could be applied to slaves.

“Anyone of these provisions in the

hands of abolition statesmen, and

backed up by a right moral sentiment,

would put an end to slavery in America,” Douglass concluded.

pro-slavery Constitution would look like

should turn to the Confederate Constitution of 1861. Though it largely mimics the Constitution,

it is replete with references to “the institution

of negro slavery,” “negroes of the African

race,” and “negro slaves.” It specifically

forbids the Confederate Congress from

passing any “law denying or impairing

the right of property in negro slaves.”