What the Constitution Really

Says About Race and Slavery

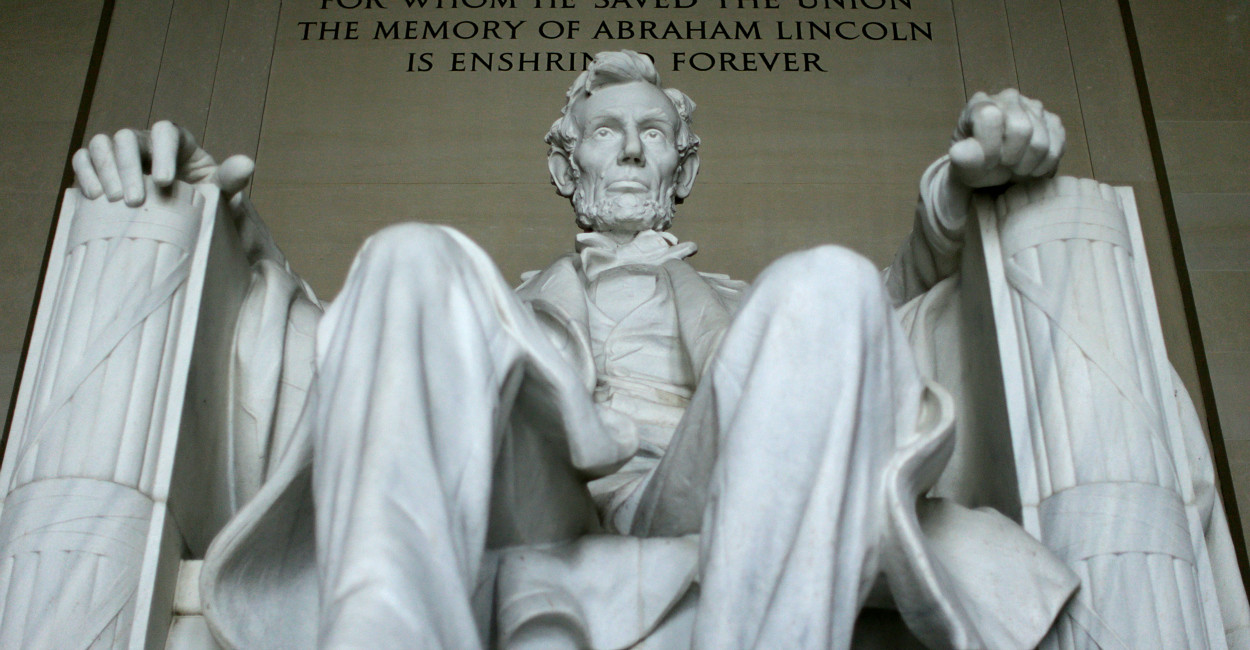

Referring to slavery, Abraham Lincoln wrote, "Thus, the thing is hid away, in the

Constitution, just as an afflicted man hides away a wen or a cancer, which he dares

not cut out at once, lest he bleed to death." (Photo: Gary Cameron/Reuters/Newscom)

Constitution, just as an afflicted man hides away a wen or a cancer, which he dares

not cut out at once, lest he bleed to death." (Photo: Gary Cameron/Reuters/Newscom)

One hundred and fifty years ago

this month, the 13th Amendment officially

was ratified, and with it, slavery finally

was abolished in America. The New York

World hailed it as “one of the most important

reforms ever accomplished by voluntary

human agency.”

this month, the 13th Amendment officially

was ratified, and with it, slavery finally

was abolished in America. The New York

World hailed it as “one of the most important

reforms ever accomplished by voluntary

human agency.”

The newspaper said the amendment

“takes out of politics, and consigns to

history, an institution incongruous to our

political system, inconsistent with

justice and repugnant to the humane

sentiments fostered by Christian

civilization.”

“takes out of politics, and consigns to

history, an institution incongruous to our

political system, inconsistent with

justice and repugnant to the humane

sentiments fostered by Christian

civilization.”

With the passage of the 13th Amendment

—which states that “[n]either slavery

nor involuntary servitude, except as a

punishment for crime whereof the party

shall have been duly convicted, shall

exist within the United States, or any

place subject to their jurisdiction”—the

central contradiction at the heart of the

Founding was resolved.

—which states that “[n]either slavery

nor involuntary servitude, except as a

punishment for crime whereof the party

shall have been duly convicted, shall

exist within the United States, or any

place subject to their jurisdiction”—the

central contradiction at the heart of the

Founding was resolved.

Eighty-nine years after the Declaration of Independence had proclaimed all men to

be free and equal, race-based chattel

slavery would be no more in the United States.

be free and equal, race-based chattel

slavery would be no more in the United States.

While all today recognize this momentous accomplishment, many remain confused

about the status of slavery under the

original Constitution. Textbooks and

history books routinely dismiss the

Constitution as racist and pro-slavery.

The New York Times, among others,

continues to casually assert that the

Constitution affirmed African-Americans

to be worth only three-fifths of a human being.

about the status of slavery under the

original Constitution. Textbooks and

history books routinely dismiss the

Constitution as racist and pro-slavery.

The New York Times, among others,

continues to casually assert that the

Constitution affirmed African-Americans

to be worth only three-fifths of a human being.

Ironically, many Americans who are resolutely

opposed to racism unwittingly agree with

Chief Justice Roger Taney’s claim in Dred Scott v.

Sandford (1857) that the Founders’ Constitution

regarded blacks as “so far inferior that they

had no rights which the white man was

bound to respect, and that the negro

might justly and lawfully be reduced to

slavery for his benefit.” In this view, the

worst Supreme Court case decision in

American history was actually correctly

decided.

opposed to racism unwittingly agree with

Chief Justice Roger Taney’s claim in Dred Scott v.

Sandford (1857) that the Founders’ Constitution

regarded blacks as “so far inferior that they

had no rights which the white man was

bound to respect, and that the negro

might justly and lawfully be reduced to

slavery for his benefit.” In this view, the

worst Supreme Court case decision in

American history was actually correctly

decided.

The argument that the Constitution is racist suffers from one fatal flaw: the concept of race does not exist in the Constitution.

Such arguments have unsettling implications

for the health of our republic. They teach

citizens to despise their founding charter

and to be ashamed of their country’s origins.

They make the Constitution an object of

contempt rather than reverence. And they

foster alienation and resentment among

African-American citizens by excluding them

from our Constitution.

for the health of our republic. They teach

citizens to despise their founding charter

and to be ashamed of their country’s origins.

They make the Constitution an object of

contempt rather than reverence. And they

foster alienation and resentment among

African-American citizens by excluding them

from our Constitution.

The received wisdom in this case is wrong.

If we turn to the actual text of the Constitution

and the debates that gave rise to it, a

different picture emerges. The case for

a racist, pro-slavery Constitution

collapses under closer scrutiny.

If we turn to the actual text of the Constitution

and the debates that gave rise to it, a

different picture emerges. The case for

a racist, pro-slavery Constitution

collapses under closer scrutiny.

Race and the Constitution

The argument that the Constitution is

racist suffers from one fatal flaw: the

concept of race does not exist in the

Constitution. Nowhere in the Constitution

—or in the Declaration of Independence,

for that matter—are human beings

classified according to race, skin color,

or ethnicity (nor, one should add, sex,

religion, or any other of the left’s

favored groupings). Our founding

principles are colorblind (although

our history, regrettably, has not been).

racist suffers from one fatal flaw: the

concept of race does not exist in the

Constitution. Nowhere in the Constitution

—or in the Declaration of Independence,

for that matter—are human beings

classified according to race, skin color,

or ethnicity (nor, one should add, sex,

religion, or any other of the left’s

favored groupings). Our founding

principles are colorblind (although

our history, regrettably, has not been).

The Constitution speaks of people,

citizens, persons, other persons (a

euphemism for slaves) and Indians

not taxed (in which case, it is their

tax-exempt status, and not their skin

color, that matters). The first

references to “race” and “color”

occur in the 15th Amendment’s

guarantee of the right to vote, ratified in 1870.

citizens, persons, other persons (a

euphemism for slaves) and Indians

not taxed (in which case, it is their

tax-exempt status, and not their skin

color, that matters). The first

references to “race” and “color”

occur in the 15th Amendment’s

guarantee of the right to vote, ratified in 1870.

A newly freed group of black men and a few children pose by

a canal against the ruins of Richmond, Va., after Union troops

took the city on April 3, 1865. (Photo: Everett Collection/Newscom)

a canal against the ruins of Richmond, Va., after Union troops

took the city on April 3, 1865. (Photo: Everett Collection/Newscom)

The infamous three-fifths clause, which

more nonsense has been written than any

other clause, does not declare that a black

person is worth 60 percent of a white person.

It says that for purposes of determining the

number of representatives for each state in

the House (and direct taxes), the government

would count only three-fifths of the slaves,

and not all of them, as the Southern states,

who wanted to gain more seats, had insisted.

The 60,000 or so free blacks in the North and

the South were counted on par with whites.

more nonsense has been written than any

other clause, does not declare that a black

person is worth 60 percent of a white person.

It says that for purposes of determining the

number of representatives for each state in

the House (and direct taxes), the government

would count only three-fifths of the slaves,

and not all of them, as the Southern states,

who wanted to gain more seats, had insisted.

The 60,000 or so free blacks in the North and

the South were counted on par with whites.

Contrary to a popular misconception, the

Constitution also does not say that only

white males who owned property could vote.

The Constitution defers to the states to

determine who shall be eligible to vote

(Article I, Section 2, Clause 1). It is a little

known fact of American history that black

citizens were voting in perhaps as many

as 10 states at the time of the founding

(the precise number is unclear, but only

Georgia, South Carolina, and Virginia

explicitly restricted suffrage to whites).

Constitution also does not say that only

white males who owned property could vote.

The Constitution defers to the states to

determine who shall be eligible to vote

(Article I, Section 2, Clause 1). It is a little

known fact of American history that black

citizens were voting in perhaps as many

as 10 states at the time of the founding

(the precise number is unclear, but only

Georgia, South Carolina, and Virginia

explicitly restricted suffrage to whites).

Slavery and the Constitution

Not only does the Constitution not mention

blacks or whites, but it also doesn’t

mention slaves or slavery. Throughout

the document, slaves are referred to as

persons to underscore their humanity.

As James Madison remarked during the

constitutional convention, it was “wrong

to admit in the Constitution the idea that

there could be property in men.”

blacks or whites, but it also doesn’t

mention slaves or slavery. Throughout

the document, slaves are referred to as

persons to underscore their humanity.

As James Madison remarked during the

constitutional convention, it was “wrong

to admit in the Constitution the idea that

there could be property in men.”

The Constitution refers to slaves using

three different formulations: “other persons”

(Article I, Section 2, Clause 3), “such

persons as any of the states now existing

shall think proper to admit” (Article I,

Section 9, Clause 1), and a “person

held to service or labor in one state, under

the laws thereof” (Article IV, Section 2, Clause 3).

three different formulations: “other persons”

(Article I, Section 2, Clause 3), “such

persons as any of the states now existing

shall think proper to admit” (Article I,

Section 9, Clause 1), and a “person

held to service or labor in one state, under

the laws thereof” (Article IV, Section 2, Clause 3).

Although these circumlocutions may not

have done much to improve the lot of

slaves, they are important, as they

denied constitutional legitimacy to the

institution of slavery. The practice

remained legal, but slaveholders could

not invoke the supreme law of the land

to defend its legitimacy. These formulations

make clear that slavery is a state institution

that is tolerated—but not sanctioned—

by the national government and the

Constitution.

have done much to improve the lot of

slaves, they are important, as they

denied constitutional legitimacy to the

institution of slavery. The practice

remained legal, but slaveholders could

not invoke the supreme law of the land

to defend its legitimacy. These formulations

make clear that slavery is a state institution

that is tolerated—but not sanctioned—

by the national government and the

Constitution.

Reading the original Constitution, a

visitor from a foreign land would simply

have no way of knowing that race-based

slavery existed in America. As Abraham

Lincoln would later explain:

visitor from a foreign land would simply

have no way of knowing that race-based

slavery existed in America. As Abraham

Lincoln would later explain:

Thus, the thing is hid away, in the

Constitution, just as an afflicted man

hides away a wen or a cancer, which

he dares not cut out at once, lest he

bleed to death.

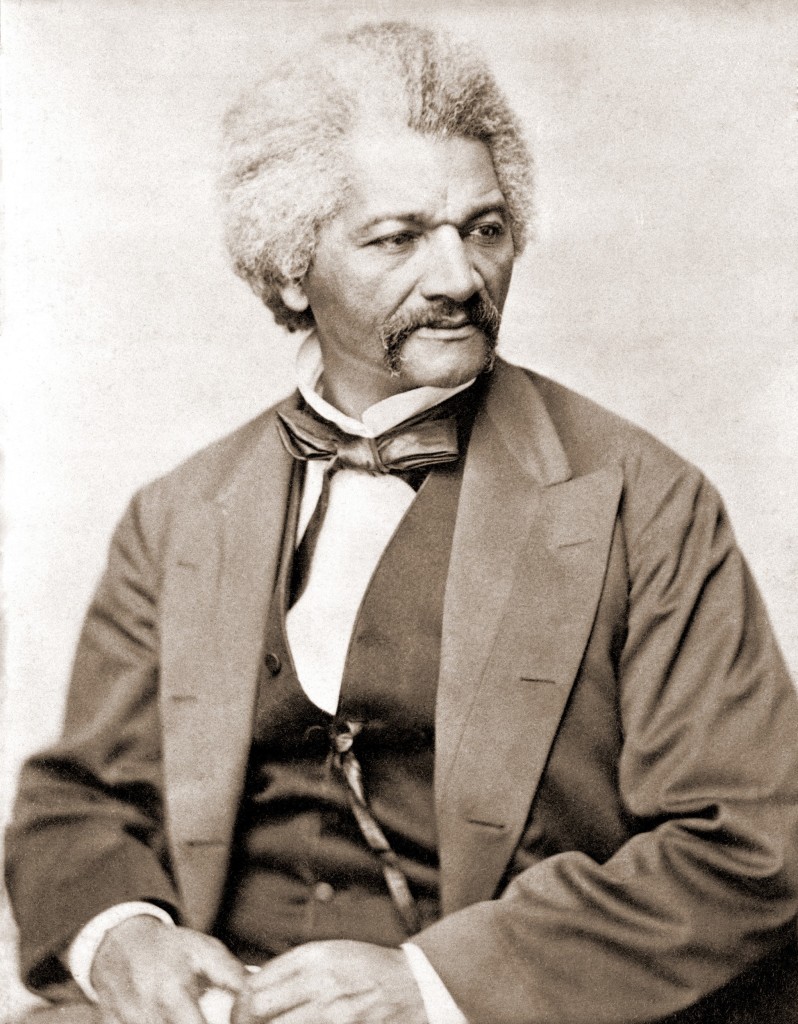

One could go even further and argue, as

Frederick Douglass did in the lead-up to the

Civil War, that none of the clauses of the

Constitution should be interpreted as

applying to slaves. The “language of the

law must be construed strictly in favor

of justice and liberty,” he argued.

Frederick Douglass did in the lead-up to the

Civil War, that none of the clauses of the

Constitution should be interpreted as

applying to slaves. The “language of the

law must be construed strictly in favor

of justice and liberty,” he argued.

Because the Constitution does not

explicitly recognize slavery and does

not therefore admit that slaves were

property, all the protections it affords

to persons could be applied to slaves.

“Anyone of these provisions in the

hands of abolition statesmen, and

backed up by a right moral sentiment,

would put an end to slavery in America,” Douglass concluded.

explicitly recognize slavery and does

not therefore admit that slaves were

property, all the protections it affords

to persons could be applied to slaves.

“Anyone of these provisions in the

hands of abolition statesmen, and

backed up by a right moral sentiment,

would put an end to slavery in America,” Douglass concluded.

Those who want to see what a racist and

pro-slavery Constitution would look like

should turn to the Confederate Constitution of 1861. Though it largely mimics the Constitution,

it is replete with references to “the institution

of negro slavery,” “negroes of the African

race,” and “negro slaves.” It specifically

forbids the Confederate Congress from

passing any “law denying or impairing

the right of property in negro slaves.”

pro-slavery Constitution would look like

should turn to the Confederate Constitution of 1861. Though it largely mimics the Constitution,

it is replete with references to “the institution

of negro slavery,” “negroes of the African

race,” and “negro slaves.” It specifically

forbids the Confederate Congress from

passing any “law denying or impairing

the right of property in negro slaves.”

Contrary to a popular misconception, the Constitution also does not say that only white males who owned property could vote.

One can readily imagine any number of clauses that could have been added to our Constitution to enshrine slavery. The manumission of slaves could have been prohibited. A national right to bring one’s slaves to any state could have been recognized. Congress could have been barred from interfering in any way with the transatlantic slave trade.

It is true that the Constitution of 1787 failed to abolish slavery. The constitutional convention was convened not to free the slaves, but to amend the Articles of Confederation. The slave-holding states would have never consented to a new Constitution that struck a blow at their peculiar institution. The Constitution did, however, empower Congress to prevent its spread and set it on a course of extinction, while leaving the states free to abolish it within their own territory at any time.

Regrettably, early Congresses did not pursue a consistent anti-slavery policy. This, however, is not an indictment of the Constitution itself. As Frederick Douglass explained: “A chart is one thing, the course of a vessel is another. The Constitution may be right, the government wrong.”

Congress and the Slave Trade

In his original draft of the Declaration of Independence, Thomas Jefferson called the African slave trade an “execrable commerce” and an affront “against human nature itself.” Because of a concession to slave-holding interests, the Constitution stipulates that it may not be abolished “prior to the year one thousand eight hundred and eight” (Article I, Section 9, Clause 1).

Before the Civil War, Frederick Douglass said that nothing in the Constitution should be interpreted as applying to slaves. The “language of the law must be construed strictly in favor of justice and liberty,” he argued. (Photo: Everett Collection/Newscom)

In the meantime, Congress could discourage the importation of slaves from abroad by imposing a duty “not exceeding 10 dollars on each person” (Article I, Section 9, Clause 1). Although early Congresses considered such measures, they were never enacted.

Early Congresses did, however, regulate the transatlantic slave trade, pursuant to their power “to regulate commerce with foreign nations” (Article I, Section 8, Clause 3). In 1794, 1800, and 1803, statutes were passed that severely restricted American participation in it. No American shipyard could be used to build ships that would engage in the slave trade, nor could any ship sailing from an American port traffic in slaves abroad. Americans were also prohibited from investing in the slave trade.

Finally, on the very first day on which it was constitutionally permissible to do so—Jan. 1, 1808—the slave trade was abolished by law.

The law, which President Thomas Jefferson signed, stipulated stiff penalties for any American convicted of participating in the slave trade: up to $10,000 in fines and five to 10 years in prison. In 1823, a new law was passed that punished slave-trading with death.

Congress and the Expansion of Slavery

Banning the importation of slaves would not by itself put an end to slavery in the United States. Slavery would grow naturally even if no new slaves were brought into the country.

Although Congress could not prevent this, it could prevent slavery from spreading geographically to the territories from which new states would eventually be created.

Congress has the power “to dispose of and make all needful rules and regulations respecting the territory or other property belonging to the United States” (Article IV, Section 3, Clause 2), to forbid the migration of slaves into the new territories (Article I, Section 9, Clause 1), and to stipulate conditions for statehood (Article IV, Section 3, Clause 2).

In no way could the Constitution be said to be pro-slavery. The principles of natural right undergirding it are resolutely anti-slavery. Its language conveys disapproval of slavery.

Regrettably, early Congresses did not prevent the spread of slavery. Between 1798 and 1822, Congress enacted 10 territorial acts. Only half excluded slavery.

As a result, seven slaveholding states and five free states were admitted into the union. The seeds of what Abraham Lincoln would later call the crisis of the house divided were sown.

Slavery in the Existing States

As for the existing slaveholding states that had ratified the Constitution, what could Congress do to restrict the growth of slavery within their borders? Here Congress had more limited options. After 1808, “the migration” of slaves across state lines could have been prohibited (Article I, Section 9, Clause 1). This was never done.

In principle, slavery could have been taxed out of existence. However, the requirement that direct taxes be apportioned among the states made it impossible to exclusively target slaveholders. A capitation or head tax, for example, even though it would have been more costly for Southerners, would also impose a heavy burden on Northerners.

While one could perhaps have circumvented the apportionment requirement by calling for an indirect tax on slaves—as Sen. Charles Sumner, R-Mass., would later doduring the Civil War—such arguments were not made in the early republic.

There was one clause in the original Constitution that required cooperation with slaveholders and protected the institution of slavery. Slaves who escaped to freedom were to “be delivered up” to their masters (Article IV, Section 2, Clause 3). The motion to include a fugitive slave clause at the constitutional convention passed unanimously and without debate. This would seem to indicate that all knew it would be futile to try to oppose such a measure.

The debate instead focused on the wording. Whereas the original draft had referred to a “person legally held to service or labor in one state,” the final version instead refers to a “person held to service or labor in one state, under the laws thereof.” This change, Madison explains in his notes, was to comply “with the wish of some who thought the term legalequivocal,” as it gave the impression “that slavery was legal in a moral view,” rather than merely permissible under the law.

This remark by Madison captures the Constitution’s stance vis-à-vis slavery: permissible, but not moral. Legal, but not legitimate.

In no way can the Constitution be said to be pro-slavery. The principles of natural right undergirding it are resolutely anti-slavery. Its language conveys disapproval of slavery. And it contains within it several provisions that could have been and were at times used to prevent the spread of slavery.

This may not make it an anti-slavery Constitution. But even before the 13th Amendment, it was a Constitution that, if placed in the right hands, could be made to serve the cause of freedom.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Thanks for commenting. Your comments are needed for helping to improve the discussion.